“How can fiction help us cope with our world?”

It hurts to read the news these days.

It hurts my brain, it hurts my heart. I can only read so much before I have to tune out, move on with my day. It’s not that I don’t want to know and understand what’s going on in our country and in our world—I do, of course I do. Awareness is the first step at enabling any kind of change. But still, I have a mental and emotional limit. There is only so much suffering my brain can absorb.

The speed of the news is part of it—every day a revolving flow of red letter, all cap headlines. We expect that in 2016; the Internet and social media have buoyed our expectations for fresh, compelling content. We mindlessly pick up our phones all day, refreshing our feeds: Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, repeat. Our phones are with us as soon as we wake up in the morning, right before we close our eyes at night. Even without directly checking news sites, the news reaches us, always. Our friends are talking about the latest shooting, the latest bombing, gun laws and foreign policies. Everyone has an opinion—and that’s great. It’s how it should be. Conversations are necessary, and the best way for each and every one of us to keep on learning, to keep on pushing and evolving our perspectives.

But what is our emotional limit? Week after week, day after day, it’s something new, something equally or more shocking than we’ve seen before, more graphic and uncensored. More real.

I worry that I’m becoming numb.

The names and faces fade so quickly. Too quickly. When the violence in Orlando happened, I felt sick, heartbroken that my own book, TRANSCENDENT, targets that same city. In my book, Disney World is the target—fiction that blurs scarily close to reality.

But already, just a few months later, Orlando and Pulse feel so long ago. We’ve had so much tragedy to face since then. We read the names, we stare at the faces. We try to imagine their families. We wonder about the life they’ll now never get to live. And then the next day, or the next week, there are new faces. The old faces, unintentionally, unconsciously, are hazier. Less vivid.

No place is immune. Orlando could be any city, every city. This is our reality now. We need some outlet for our fear—we need to find a way to still have hope.

So what can we do when we see too much, feel too much? How can teens in particular cope, begin to process and understand what is happening in their world—their present and their future?

For me at least, I turn to books. Fiction, stories, people and places who are only real in my imagination. Because sometimes it takes stepping out of reality, the day to day, to understand what is actually happening around me, and my place in it.

Books… they slow us down. They show us new perspectives, challenge our beliefs. In reading we can intimately identify with characters, individuals—like people we know, and more importantly, like people we don’t yet know. People we’ve never met in our small towns, or even in our big cities. But even in the differences, we (at least in a good book) can see things in them that speak to our own lives, our own fears and dreams.

Through books we question, we learn, we grow.

And, hopefully, we leave each story with a new understanding of our real world—a new appreciation of all the beautiful people in it—and a renewed sense of hope. Because more hate will not solve our problems. More hate will never solve anything. There is common ground that connects all of us, the deepest core of what makes us human. Books can help us—enable us to appreciate our similarities, and to celebrate what makes us all unique.

We can all be pieces of the solution. We can take the negative and react in positive ways—turn the bad news to good. We don’t have to give up, give in. It’s a message that’s important for our young people especially: Reach out to others. Help your community. Talk to someone new. Start small.

Because small things become big things, and big things can change our world.

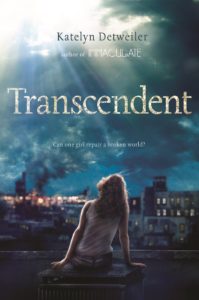

Transcendent

Author: Katelyn Detweiler

Published October 4th, 2016 by Viking Books for Young Readers

About the Book: A beautiful work of magical realism, a story about a girl in the real world who is called upon to be a hero.

When terrorists bomb Disney World, seventeen-year-old Iris Spero is as horrified as anyone else. Then a stranger shows up on her stoop in Brooklyn, revealing a secret about the mysterious circumstances surrounding Iris’s birth, and throwing her entire identity into question. Everything she thought she knew about her parents, and about herself, is a lie.

Suddenly, the press is confronting Iris with the wild notion that she might be “special.” More than just special: she could be the miracle the world now so desperately needs. Families all across the grieving nation are pinning their hopes on Iris like she is some kind of saint or savior. She’s no longer sure whom she can trust—except for Zane, a homeless boy who long ago abandoned any kind of hope. She knows she can’t possibly be the glorified person everyone wants her to be… but she also can’t go back to being safe and anonymous. When nobody knows her but they all want a piece of her, who is Iris Spero now? And how can she—one teenage girl—possibly heal a broken world?

About the Author: Katelyn Detweiler was born and raised in a small town in eastern Pennsylvania, living in a centuries-old farmhouse surrounded by fields and woods. She spent the vast majority of childhood with her nose in a book or creating make-believe worlds with friends, daydreaming about how she could turn those interests into an actual paying career. After graduating from Penn State University with a B.A. in English Literature, emphasis in Creative Writing and Women’s Studies, she packed her bags and made the move to New York City, determined to break into the world of publishing. She worked for two years in the marketing department of Macmillan Children’s Group before moving in 2010 to the agency side of the business at Jill Grinberg Literary, where she is currently a literary agent representing books for all ages and across all genres.

Katelyn lives, works, and writes in Brooklyn, playing with words all day, every day, her dream come true. When she’s not reading or writing, Katelyn enjoys yoga, fancy cocktails, and road trips. She frequently treks back to her hometown in Pennsylvania, a lovely green escape from life in the city, and her favorite place to write.

Q&A WITH KATELYN DETWEILER

How did you come to write TRANSCENDENT?

My earliest, vague conception of the book was that it would start with an unprecedented tragedy, a state of international heartbreak and desperation so raw that the world would be at a total loss for what next—looking to anything, anyone, to bring stability or clarity or hope. I knew, too, that whatever the tragedy would be, it had to center on children. We can all recall how we felt when we heard about Sandy Hook. A mass shooting is horrifying no matter who the victims are—but targeting children? I couldn’t stop watching the news updates, staring at the faces of the students who’d been killed, thinking about the futures they would never have, the families left behind. It was this memory that guided me here—the question of what could be so completely awful that people might actually stand still. Might remember, might keep remembering. For TRANSCENDENT, I chose a bombing. Disney World. I knew that my mind would have to go to dark places, that things had to get worse before they could get better. But it felt necessary to me, starting these conversations—and it feels more necessary, more relevant today than ever.

Did you write it with the 15th anniversary of 9/11 in mind?

It was completely unintentional, though the timing seems hugely important to me now. I was in high school when the towers were hit. It felt like such a terrible, extraordinary, surreal event at the time. It was the beginning—to my mind, at least—of a new era of terrorism, of that terrible state of wondering what awful tragedy would hit next. Teens today don’t know another reality outside of our current world; they’ve grown up in a place where acts of terrorism and mass shootings have become the norm. I was especially horrified when the Pulse shooting happened, to think that I’d targeted Orlando, too, in this book. But really, by the time it publishes, who knows how many other cities could be on the list of victims? No place is immune. Orlando could be any city, every city. This is our reality now. We need some outlet for our fear—we need to find a way to still have hope.

One of the big themes in the book is hope and forgiveness overcoming hate and despair. Can you talk more about that and why it’s so relevant for young people today?

It’s hard sometimes to not react to hate with more hate. To blindly lash out, hurt whoever hurt you, ensure justice is served. We see this in our personal lives. And we see it so often on an international scale—the fear that terrorism causes, the desperation. The feeling of weakness that can morph into something quite ugly, spawn intolerance for people who look a certain way, talk a certain way, pray a certain way. People desperately seek a target, someone to point a finger at—even if that blame is unjust, irrational. But we cannot sink to that level. More hate will not solve the problem. More hate won’t make terrorism go away. Young people are still just formulating their opinions about the world, about others—struggling with who they are, who they want to be. They are still figuring out the role they’ll play in the world, their responsibilities—“Can I make a difference?” How they learn to find answers to these questions helps to shape and strengthen their identity, their (our) future.

Is it important for people to believe in miracles and to have faith in difficult times?

I believe that in difficult times more than ever, people look for something bigger—they want to believe that the world is not as black and white as it seems, that there is hope to be found beyond our everyday existence. Faith isn’t necessarily about believing in God, or any god, some supreme being up in the clouds. It can be, sure, for some. But it can also be about trusting in yourself, in your family and/or your friends, in the love you choose to surround yourself with, the connections you make with the world around you. There’s a quote that opens IMMACULATE, attributed to Albert Einstein: “There are only two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is.” I love this idea—this thought that we’re just too jaded to realize how many tiny miracles are around us every day, even in the ugliest, darkest times. Life is a miracle. We’re miracles. We’re more than just our cells and our DNA.

This story, like your previous book IMMACULATE, is centered on a virgin birth. Why did you choose to explore that topic? Is TRANSCENDENT a religious book?

I’ve been fascinated by the idea of a pregnant virgin in contemporary times for years now, ever since I was a teenager and asked my own mom: would you believe me if I said I was a pregnant virgin? She said yes. She would believe me. It stuck with me, the idea that faith—whether it be in a supreme being, or in a person you love and trust dearly—can be so all encompassing. That we can still believe in something that defies all science and reason. I would say that, at this point in life, I am spiritual more so than religious, and I think the book reflects this perspective. Spirituality—to me—is believing in more than the orderly scientific rules of our world, even if we can’t explain it, even if there’s no doctrine to help us better understand. My goal for both books was to explore and question with respect for all sides; I wanted there to be something for everyone, to find the commonalities that unite people of different faiths (or no faiths) rather than the differences.

Why was it important for this story to take place in Brooklyn?

I knew from the outset that I wanted the backdrop of Brooklyn—that a more sheltered, traditional small town wouldn’t do. Iris didn’t just grow up reading about the wider world in books or hearing about it on TV. She’s experienced it firsthand. She’s been exposed to all different kinds of people, seen lives and cultures that are so different than hers. This felt necessary to me in building a protagonist who was comfortable enough—empathetic enough, compassionate enough, bold enough—to step up to the plate, to be a voice of change. I grew up in a small town (surrounded by fields and woods rather than people and skyscrapers) and moved to NYC eight years ago, Brooklyn specifically for the last few. Living here has heightened my awareness of the world. A lot of things were so much more theoretical to me before—poverty and homelessness, for example. Different religions, different races, different cultures. I wanted a true microcosm for this story, a more accurate, complex representation of our world.

What role do race and privilege play in the book?

Privilege is key in all threads of the novel. To start: Disney is attacked because of the vast privilege it represents. This is not a park, a destination, for everyone. This is for a select, elite group. A fairytale that is unobtainable to so many—a tangible way of separating out the haves and the have-nots.

Iris herself is an upper middle class white teenager in Brooklyn. Though she’s open minded and aware of the disparity around her—volunteering at a soup kitchen, engaging with the homeless—she’s still very much in her own bubble. Iris’s Brooklyn is the version we see across the media: farmers markets and organic everything, beautiful old brownstones, hip, industrial-looking bars and restaurants, pretty white people with beards and buns and bicycles. Iris has accepted this privilege as normal, more or less, until for the first time the guarantees of her life come into question. Iris ends up at a homeless shelter; she’s confronted by a side of Brooklyn that she’d only glimpsed at surface-level before. Iris must question basic assumptions about herself—and others—as she struggles with how to reorient her life.

Do you think there’s value in exploring these ideas fictionally, vs. conversations that start from live news, internet articles, social media, etc. around current events?

Our perception of current events today is so heavily influenced by the speed of news, the internet and social media generally, the constant demand for fresh, compelling content; we’re blasted with horrific tragedies every week—becoming increasingly graphic and uncensored, as evidenced by the streaming video we saw of Philando Castile, dying after being shot by a cop. Week after week, day after day, it’s something new, something equally or more shocking than we’ve seen before. We’re becoming so numb—the names and faces fade so quickly. Already, Orlando and Pulse feel so long ago. We’ve had so much tragedy to face since then. Our brains can only absorb so much pain and suffering. I think it sometimes takes stepping *out* of our reality—our day to day—into literature (or movies, TV, etc.) to fully process our thoughts, to make sense of how we feel, what role we could possibly have in change. Books slow us down, show us new perspectives, challenge our beliefs. In reading we can intimately identify with characters, individuals—see something in them that speaks to our own lives, our own fears and dreams. And, hopefully, we leave books with a new understanding of our real world—and a new resilience.

Thank you Katelyn for this hope-filled and truthful post!