“The Writing Process”

Over the course of a career in children’s book publishing, I’ve had the opportunity to hear many wonderful authors speak about their “process” – how they approach that intimidating blank page – whether a notebook, a sheet of paper in a typewriter, or the screen on a computer. Where do you begin? And then what?

The clearest answer for me was a comment Walter Dean Myers made in a speech. “Writers write,” he said. That is the literary version of “just do it!” When you have an idea that’s taken hold of you, start writing. What you write probably won’t make it into the final version of your project, but it will help you exercise your writing muscles and fire up the connection between your thoughts and your fingers. While doing that, some good sentences will emerge; characters will introduce themselves to you; plots will begin to take shape.

This is not to say that you shouldn’t be thinking about all these elements, too – not just waiting for them to tap you on the shoulder. Make notes. Do research. Ask questions of yourself and search for answers. All of this becomes the soil your story needs to grow. But keep writing through it all. That’s the only way I know of to discover the voice that is right for this particular story – and voice is the hardest part to explain, or force, or fake.

For the three novels in my Raccoon River Kids series of chapter books, I started with a place – a small town where kids have lots more freedom than they do in cities – a place where they can hop on their bikes and go by themselves – even when they are as young as seven or eight — to a friend’s house or venture into the center of town with a park as its centerpiece, a community center, and an old town hall where the doors are always open.

That was the beginning. My early writing was about the town itself, but as I described its geography and places, I began to envision the children who would be at the center of the novels: a third-grade boy and his best friend, a third-grade girl. There was a third boy. too. He stood outside of things and had only contrary remarks about the other children’s plans. I didn’t know why at first, and I knew I would have to explain it – first to myself, then to my characters, and finally to my readers, of course.

As I developed Raccoon River and the characters in my early unstructured doodling, I also found the voice for these books. At first I thought I would have the older sibling of one of the characters be the narrator, but it became complicated. She couldn’t be everywhere the kids were. And, if she had to be involved in everything that they did, the children could never keep a secret from her. And secrets are important to children of this age – I didn’t want to take that option away from “my kids.”

I decided on an omniscient narrator who could get into everyone’s head; a teller who could be behind the scenes and in front of them simultaneously; a non-judgmental, trustworthy observer with a sympathetic view and faith in the characters.

With all these puzzle pieces to manipulate, I started to write. I always begin at the beginning. Opening chapters are important to me. Wiser authors have told me that I should never get attached to the opening I write. They universally agree that as the story progresses, beginnings often need to be changed, or moved elsewhere, or simply dropped. I’m sure that’s true, but I can’t get going until I have at least my opening scene written.

Writers have also advised me not to polish any writing until the entire first draft is written. Again, I’m sure this is good advice. But I find it impossible not to fix something that isn’t working – whether it’s an ugly phrase, a bad choice of a word, or an entire episode that is … well … wrong. The first thing I do when I return to a work-in-progress is read what I wrote the last writing session. And make changes, sometimes big ones, sometimes little tweaks. That gets me back into the voice of the story.

I write mostly chronologically. But not always. If some later adventure has been working itself out as I take walks or make dinner or watch the news, I write it out of order. I figure it will fit in somewhere. Mostly it does.

When I have a good portion of the whole written, I step away for several weeks. I might jot down notes if any random ideas come to me, but I don’t put them into the manuscript. I try to remove myself from the story for a while. When I return to it, there’s a strange sense that it was written by someone else, which allows me to see things more clearly.

The result of this round is a new manuscript. I can move chapters around, clarify motivations, polish language, deepen my characters, and strengthen the logic in the plot that will lead readers through the novel.

At the round three stage, I work on chapter endings and beginnings to be sure the story flows through smoothly. I look for secondary themes to amplify. I examine the actions of the characters and how they speak for consistency. Similarly, I check for character traits or habits that help identify one from the next for readers. Because these are chapter books for relatively new readers, I make sure there’s not too much description but that there is enough so young readers can find themselves in Raccoon River and put themselves into the story.

And again, I step away from what I am now thinking of as “a book” for a while. If it holds together when I return some weeks later, then it’s ready for some feedback. And that’s when the process starts all over again.

About the Author: Lauren L. Wohl has had a long career in children’s book publishing. She has a degree in Library Science and has been an elementary school librarian. She served as Director of James Patterson’s ReadKiddoRead prog

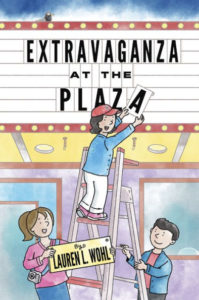

About Extravaganza at the Plaza (Raccoon River Kids #2): “It isn’t fair that our town doesn’t have its own theater,” eight-year-old Hannah complains.

A lot of thinking, planning, dreaming, and list-making, and Hannah–along with the kids of Raccoon River–are up to their ears in a brand new project: saving the town’s old abandoned Plaza Theater. But first, they have to get a look inside. And it’s spooky in there-spider webs and creaky floors, and one slowly-swaying curtain. Can Hannah and her friends save the plaza?

Lauren L. Wohl tells a story of determination and hard work, cooperation and more than little bit of luck where the kids of a small town make a real difference in their community, the first sequel to BLUEBERRY BONANZA in the RACCOON RIVER KIDS ADVENTURES series. Mark Tuchman illustrates the action with characterful drawings that enrich the tale.

Thank you, Lauren, for your post–it was fascinating to learn about your process!