“Possible Impossibilities: Magic and the Middle-Grade Reader”

When my son, Theo, was about to turn four, I asked him what he wanted for his birthday. His answer was simple, only one thing: Hogwarts Castle. “A mini tree-fort version?” I suggested hopefully. Nope, he wanted the whole thing, old stones, talking portraits, moving staircases, the whole shebang, to be built in our backyard. “Or a Batcave,” he relented, seeing my expression. “If you can’t do Hogwarts, I’ll take a Batcave.”

If little kids have one super power it’s that power to believe random, wacko stuff is totally possible. And why not? Those kind of things are happening all the time in their worlds: steam suddenly whistling out the spout of a kettle, crusty old seeds pushing up pale green sprouts through the dirt, clear light through faceted glass turning into rainbows. I remember clearly when I was four, hammering metal coffee cans and other bits of debris to an old flat piece of plywood to make a boat I would sail across Lake Ontario. My dad, who was sorting the laundry nearby, never told me that was not going to happen. To this day, I think that was one of the best gifts he ever gave me.

Too often, well-meaning adults rush in to help children develop a sense of perspective, an understanding of what is realistic, sealing up the cracks between the world of imagination and the more reliable, tried and true “reality.” The instinct generally comes from a good place. To protect from disappointment. To make sure the child is investing his or her precious hopes and dreams in something that might actually, in a million years, have some chance of ever happening.

“If only he would ask for something we could actually give him,” I remember bemoaning to Theo’s dad after Theo finished showing us the impossibly grandiose Batcave blueprints he had found in the back of one of his Batman books. Then I thought about my boat. About that sense of possibility. I took a deep breath. “This is too big a job for us,” I admitted to Theo. “But how would you do it?” Theo was disappointed in us. But eventually he took a shovel, went out behind the house and started to dig. His friends came over later in the week and they dug as well. And the digging has gone on sporadically from then—for about nine years now. At first it might have been about the bat cave, but as the digging went on it became about something else: about the undefined, mysterious possibilities of the hole itself. Something way better than anything we, his parents, could have cobbled together for him.

By the time kids get to the middle grades, the concept “real” becomes very important. “Is that real gold?” “That is sooooo fake!” At the same time, this age is also the sweet spot for the greatest magical literature ever written: Harry Potter; The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe; The Hobbit; The Dark Also Rises. The other day, my ten-year-old, Nicholas (one of the biggest realists I know), told me that all his favorite books have some kind of magic or fantasy in them. Hardly seems a coincidence. As the concepts of reality become more practically defined and potentially limiting, fantasy allows middle-graders to keep the doors and windows open into other possibilities.

Possibilities is the key word. When your nose is stuck between the covers of a great fantasy book, it’s not because you’re so caught up with bunch of stuff that could never happen. It’s because you’ve entered a place where the outrageous and fantastical does happen and you can’t wait to see what’s going to happen next. And sometimes what happens next is someone comes along and lifts one of these possible impossibilities off the page and turns it into a reality. The Internet search engine, for example, appeared in Douglas Adam’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy long before the real version was created. Sci-fi author, Jules Verne, landed the first rocket ship on the moon in remarkably accurate detail in his novel From the Earth to the Moon over a century before the first real lunar landing occurred. Sometimes what looks like wall between fantasy and reality is actually a door.

These doorway-moments, these meeting points of the real and the fantastical, are essential in middle-grade fantasy. Sometimes these doorways are quite literal. Harry Potter’s first arrival at Platform 9 ¾. Lucy walking through the wardrobe into Narnia. Other times the doorways come through characters that are so powerfully human it’s impossible not to relate to them, even if they are a different species from a totally different place and time. For example, Bilbo Baggins, the furry-footed hobbit who longs for adventure but is so attached to domestic comforts he almost abandons his great adventure when he discovers he has left his handkerchiefs at home.

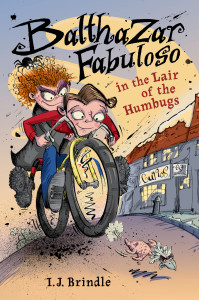

When writing my middle grade novel, Balthazar Fabuloso in the Lair of the Humbugs, the first doorway I discovered was through Balthazar’s family’s stage magic. When picking up a new bit of magic, they start by figuring out how to fake it, palming a coin to make it look like it disappeared, hiding a dove up a sleeve, etc. Only after they’ve mastered the illusion so fully it becomes second nature does the trick part fall away and the magic become real.

Some of my favorite doorway–moments as a writer come when magic doesn’t work out the way anyone planned. Unpaid bills that are folded into magical origami animals and sent flying away but wind up coming home again to demand payment. An invisibility charm that only works for as long as long as you hold your breath. Magic that is great for levitating sofas and turning puffs of smoke into baby turtles, but is totally useless for eliminating dry-rot or paying down credit card bills. In other words, magic that acts like life: messy and unpredictable, but kind of amazing at the same time.

Can magic help Balthazar get his family back after they mysteriously vanish in a sinister stage accident? Possibly, but first Balthazar must find his own magic, a journey which leads him down a rabbit hole of family secrets, unexpected friendships, surprise betrayals, sinister cliques and a few other twists and turns. A journey that is about messing up, figuring stuff out, banging into walls, overcoming limitations, and, ultimately, about making the impossible possible, although not quite in the way anyone had planned.

One of my favorite games to play on hikes and long road trips is the “what if” game. What if this forest was actually our home? What if the raindrops on the windshield all had personalities? What if that red car behind us is an evil road wizard hot on our trail? What if we could open the plane door and walk out onto the clouds? It’s all about finding the doorways, then seeing where they lead, the more unexpected the better. Sometimes they lead to a story or a sketch. Other times to complete absurdity. But they always lead somewhere. Which is why magical literature is so important to middle-graders. Not simply because of the magic itself, but because of the possibilities it opens up, possibilities which can lead anywhere.

Balthazar Fabuloso in the Lair of Humbugs

About the Book: Magic, humor and high adventure are used to reaffirm fundamental family values in this debut novel.|

Balthazar Fabuloso’s lovable and eccentric family performs a magic show. What makes the act so unusual is that all the Fabulosos actually have superhuman powers, except for Balthazar, a practical-minded 11-year-old who simply aspires to be a normal kid. So when everyone but Balthazar disappears mid performance, the only Fabuloso without real magical skills must save the family. Balthazar wonders if the family’s archrivals, the Furious Fistulas, are to blame or if there are other, even darker forces at work. To free his loved ones Balthazar must work with some questionable characters, including a lunatic long-lost uncle, three enigmatic senior citizens and the loathsome Pagan Fistula, whose family also mysteriously goes missing.

At the center of these disappearances is a force so evil that the world’s most preeminent magicians cower before it. What hope could a ragtag crew of misfits have against it?

Link to the Book: http://www.holidayhouse.com/title_display.php?ISBN=9780823435777

About the Author: I. J. Brindle is an author and screenwriter. She has also produced internet games for Disney, written and directed theater in New York and Montreal, clerked in a bookstore, waited tables, and had a bunch of other adventures along the road. She is the mother of two wild monkey children and the companion of a dog named Moose.

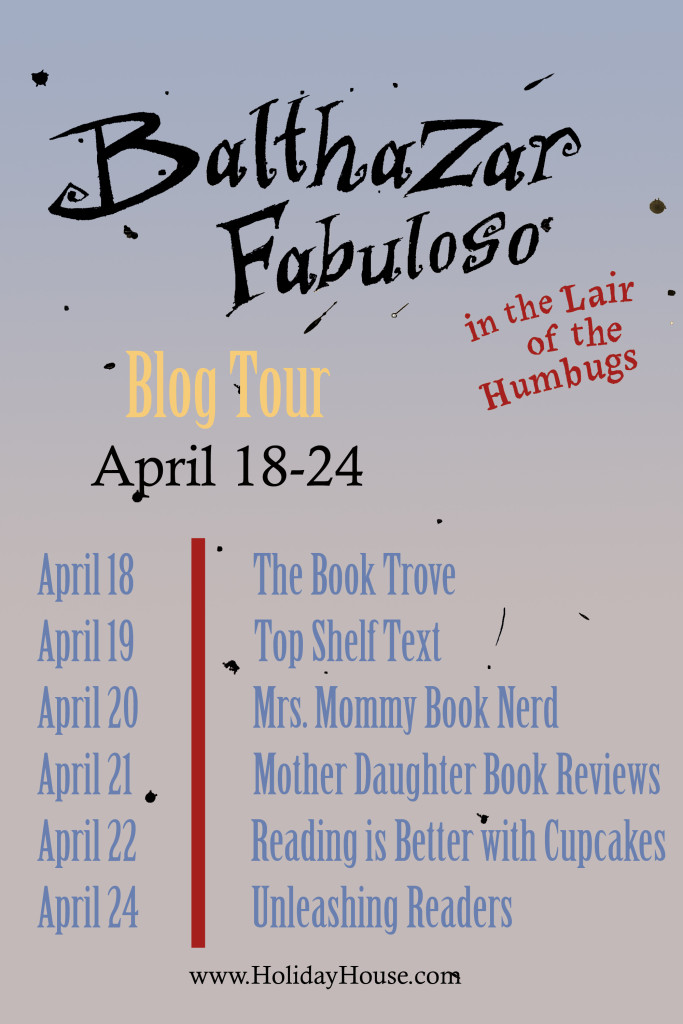

Check Out the Other Books on the Tour:

Thank you to I. J. for this important post. We hope our readers enjoyed her words as much as we did!

Thank you to Brittany at Holiday House for connecting us with I. J.!