In January, I was contacted by a publicity and marketing associate from Abrams Books/Amulet Books out of the blue. In this email, I was asked to work on a teaching guide about their graphic novels: The Misadventures of Salem Hyde, Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales, Hereville, and the Explorer series.

I was beyond honored! And, of course, I said that I would definitely love to do it as I had read all of the graphic novels, and I am a huge fan of them.

First, they asked me to write an introduction about graphic novels and their importance in the classroom. I am a huge advocate for using graphic novels in schools, so I immediately began researching and writing. Here is the introduction:

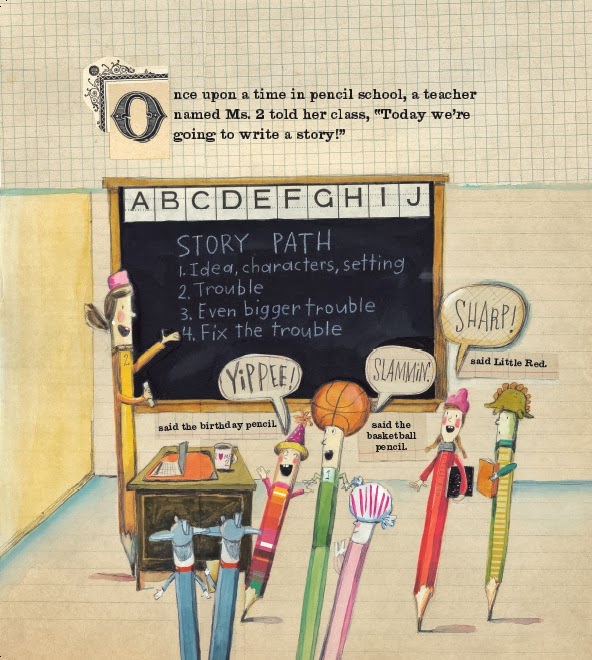

What are graphic novels? The easiest way to describe graphic novels is to say that they are book-length comic books. However, a more complex definition that educators and librarians use is “book-length narratives told using a combination of words and sequential art, often presented in comic book style” (Fletcher-Spear, 37). Graphic novels are not written in just one genre; they can be in any genre, since graphic novels are a format/medium. Graphic novels are much like novels, but they’re told through words and visuals. They have all narrative elements, including characters, a complete plot, a conflict, etc.

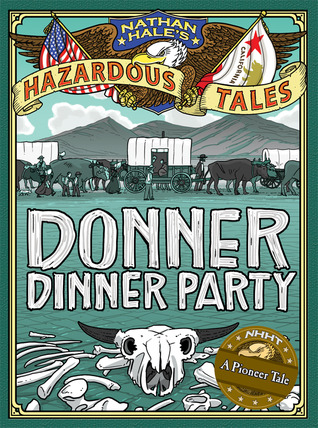

Middle grade and young adult graphic novels cover a wide spectrum of themes and topics. Some common themes found in graphic novels for this age include the hero’s journey; overcoming hardship; and finding one’s identity. For example, in Hereville, we meet Mirka, an everyday girl who learns to use her brains and brawn to overcome her foes. In The Misadventures of Salem Hyde, Salem is working on finding out just who she is (both as a witch and as a person) with the help of her friend Whammy. Graphic novels can cross curricular lines. One example is the Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales series—comical nonfiction that takes historical events and presents them in interesting ways, using graphics and humor that will make students want to learn even more about the historical time periods. In the Explorer series, stories include topics such as animal adaptation, volcanic eruptions, and the fate of humanity. Like novels, graphic novels offer opportunities in all subject areas to extend students’ thinking.

Over the past few years, graphic novels have become a hot topic, growing in popularity with both children and educators. While many teachers are beginning to include them in the classroom, there are still teachers, administrators, and librarians who struggle with including this format in their schools. So, why should you use them in your classroom and have them available for students?

- Graphic novels can make a difficult subject interesting and relatable. (Cohen)

- Students are visual learners, and today’s students have a much wider visual vocabulary than students in the past. (Karp)

- Graphic novels can help foster complex reading skills by building a bridge from what students know to what they still have to learn. (NCTE)

- Graphic novels can help with scaffolding when trying to teach higher-order thinking skills or other complex ideas.

- For students who struggle to visualize while they read, graphic novels provide visuals that shows what good readers do. (NCTE)

- Many graphic novels rely on symbol, allusion, satire, parody, irony, and characters/plot and can be used to teach these, and other, literary devices. (Miller; NCTE)

- Often, in between panels (called the gutter), the reader must make inferences to understand how the events in one panel lead to the events in the next. (McCloud)

- Graphic novels can make differentiating easier. (Miller)

- Graphic novels can help ELL (English Language Learners) and reluctant and struggling readers since they divide the text into manageable chunks, use images (which help students understand unknown vocabulary), and are far less daunting than prose. (Haines)

- Graphic novels do not reduce the vocabulary demand; instead, they provide picture support, quick and appealing story lines, and less text, which allow the reader to understand the vocabulary more easily. (Haines)

- Research shows that comic books are linguistically appropriate reading material, bearing no negative impact on school achievement or language acquisition. (Krashen)

- Students love them.

Although you can find graphic novel readers at all reading levels, graphic novels can truly be a gateway to the joys of reading for reluctant and struggling readers. Reluctant readers often find reading to be less fun than video games, movies, and other media, but many will gravitate toward graphic novels because of the visuals and the fast pace. Struggling readers will pick up graphic novels for these reasons as well but also because the graphic novel includes accommodations directly in the book: images, less text, etc.

All in all, graphic novels can interest your most reluctant and struggling readers and also extend all of your readers, including your most gifted.

Resources

- Cohen, Lisa S. “But This Book Has Pictures! The Case for Graphic Novels in an AP Classroom.” AP Central. CollegeBoard.

- Fletcher-Spear, Kristin, Merideth Jenson-Benjamin, and Teresa Copeland. “The Truth About Graphic Novels: A Format, Not a Genre.” The ALAN Review Winter (2005): 37–44.

- Haines, Jennifer. “Why Use Comics in The Classroom?” Comic Book Daily. N.p., 20 Mar. 2012.

- Karp, Jesse. “The Case for Graphic Novels in Education.” American Libraries. N.p., 1 Aug. 2011.

- Krashen, Stephen. The Power of Reading. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, Inc. 1993.

- McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics. Northampton, Mass.: Kitchen Sink, 1993.

- Miller, Andrew. “Using Graphic Novels and Comics in the Classroom.” Edutopia. N.p., 11 Jan. 2012.

- NCTE, comp. “Using Comics and Graphic Novels in the Classroom.” The Council Chronicle September (2005) http://www.ncte.org/magazine/archives/122031.

I then began reading and rereading the graphic novels and planning activities and discussion questions that could go along with each book. I was asked to come up with activities for all subjects, so this pushed me out of my comfort zone a bit; however, I loved trying to figure out how these amazing books could be used throughout all classes. Some examples:

- Salem Hyde [Science]: At the end of Spelling Trouble, Salem and Whammy have to rescue a whale, but it is done in a very unconventional way. How would real scientists rescue a whale in distress?

- Hazardous Tales [Language Arts/History]: The Provost (a British soldier) and Nathan Hale disagree about the cause of the Revolutionary War. Based on One Dead Spy, what events caused the Americans to revolt? Do you agree with the Provost or with Nathan Hale about the causes of the war? (This could also be used as a debate question in class.)

- Hereville [Math]: On pages 31–32 [of Hereville 1], Mirka is given a math problem: Three people are splitting a cake, so they cut it into thirds. But then a fourth person shows up. How can they cut the cake so that each person gets an equalamount of cake? (Mirka comes up with a solution, but are there others?) What if two more people had shown up? Three more? Four more?

- Explorer [History]: On page 84 [of The Mystery Boxes], in The Soldier’s Daughter, the man says, “War is a dark power.” Where in history have we seen war consume someone? Have there been wars that did not need to be fought? Research past wars and determine if a war was started because of the need for power or if there was a legitimate reason for it.

These are just some examples.

I am happy to share the entire teaching guide with you. It can be found at http://www.abramsbooks.com/academic-resources/teaching-guides/ along with other teaching guides. The direct link to the PDF is http://www.abramsbooks.com/pdfs/academic/GraphicNovels_TeachingGuide.pdf.

I hope you find it useful as I am very proud of it,