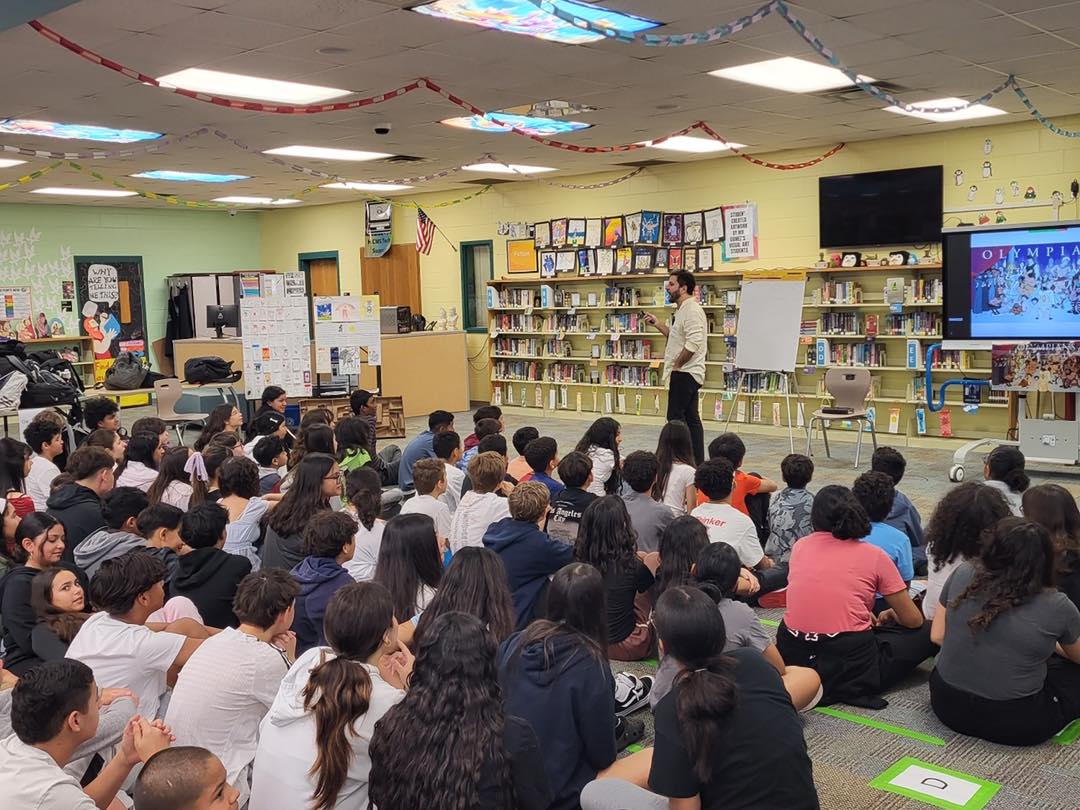

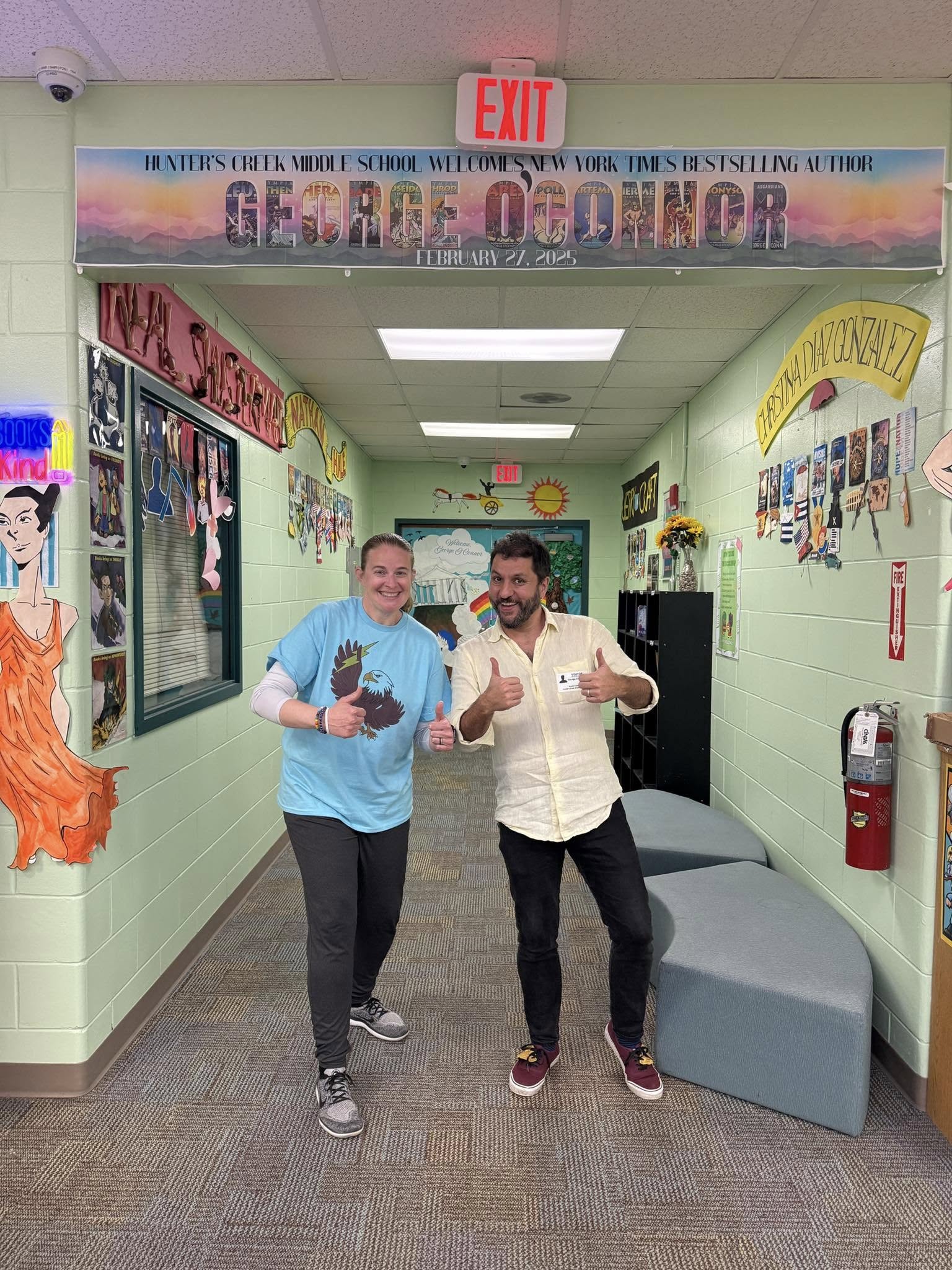

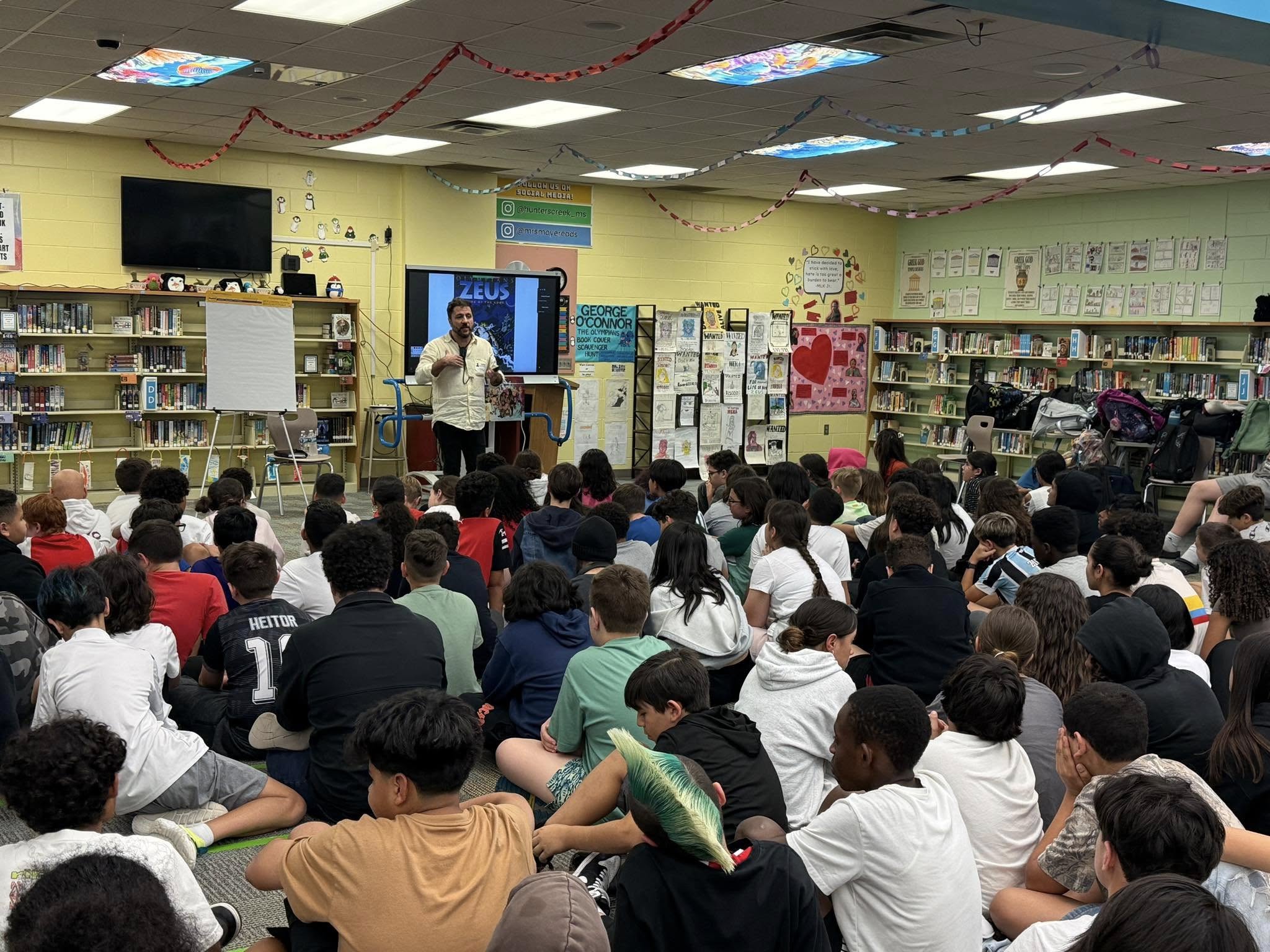

I am so lucky because my principal began an initiative at my school where we get to have an author visit our school yearly (2024: Jerry Craft, 2023: Christina Diaz Gonzalez, 2022: Nathan Hale, 2020: Neal Shusterman, 2019: Jennifer A. Nielsen). The author sees all students in the school, so it is a great community literacy event for my school, and I love being able to bring this experience to all of my students each year!

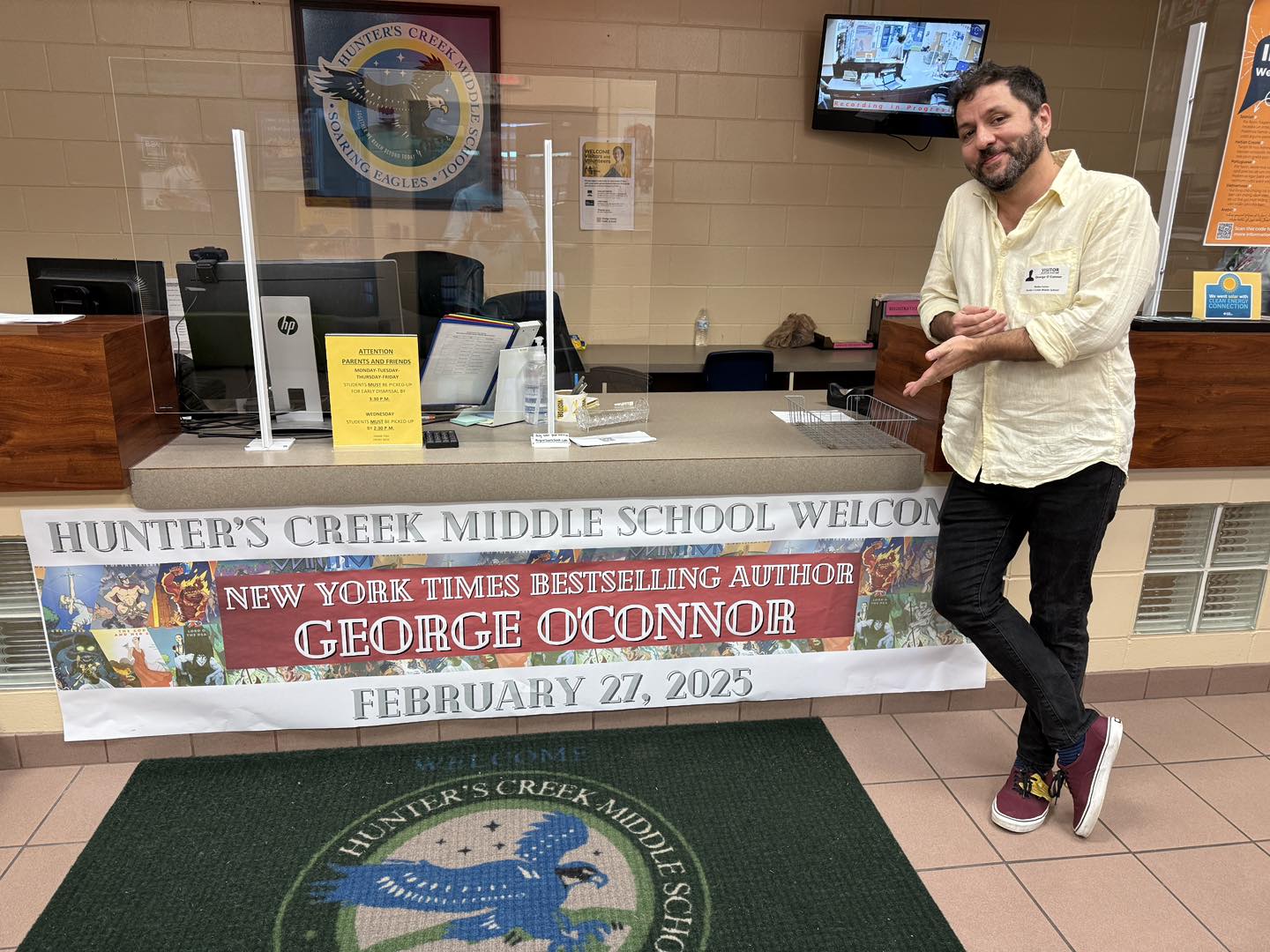

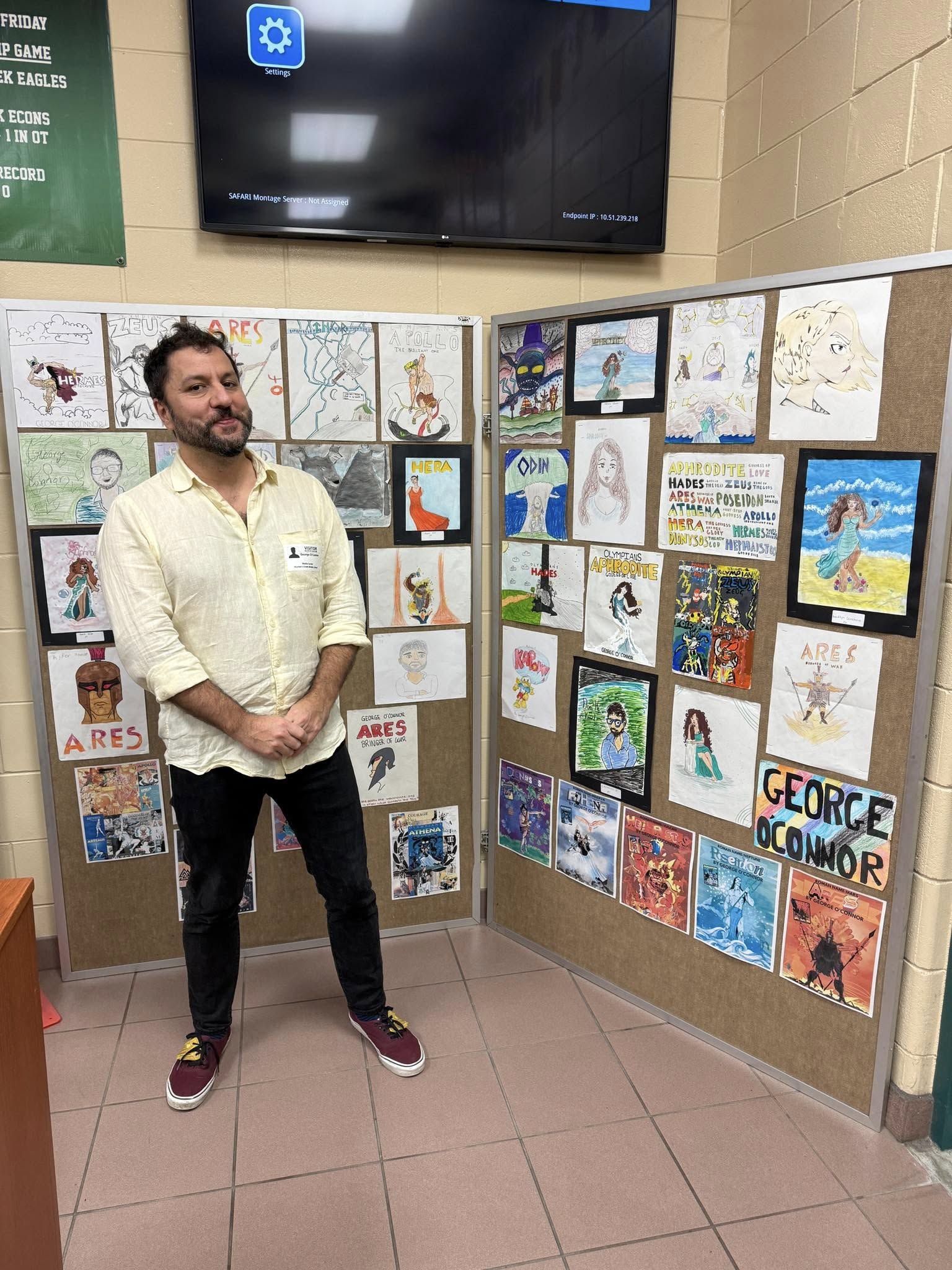

This year, we hosted New York Times Best-selling Author George O’Connor!

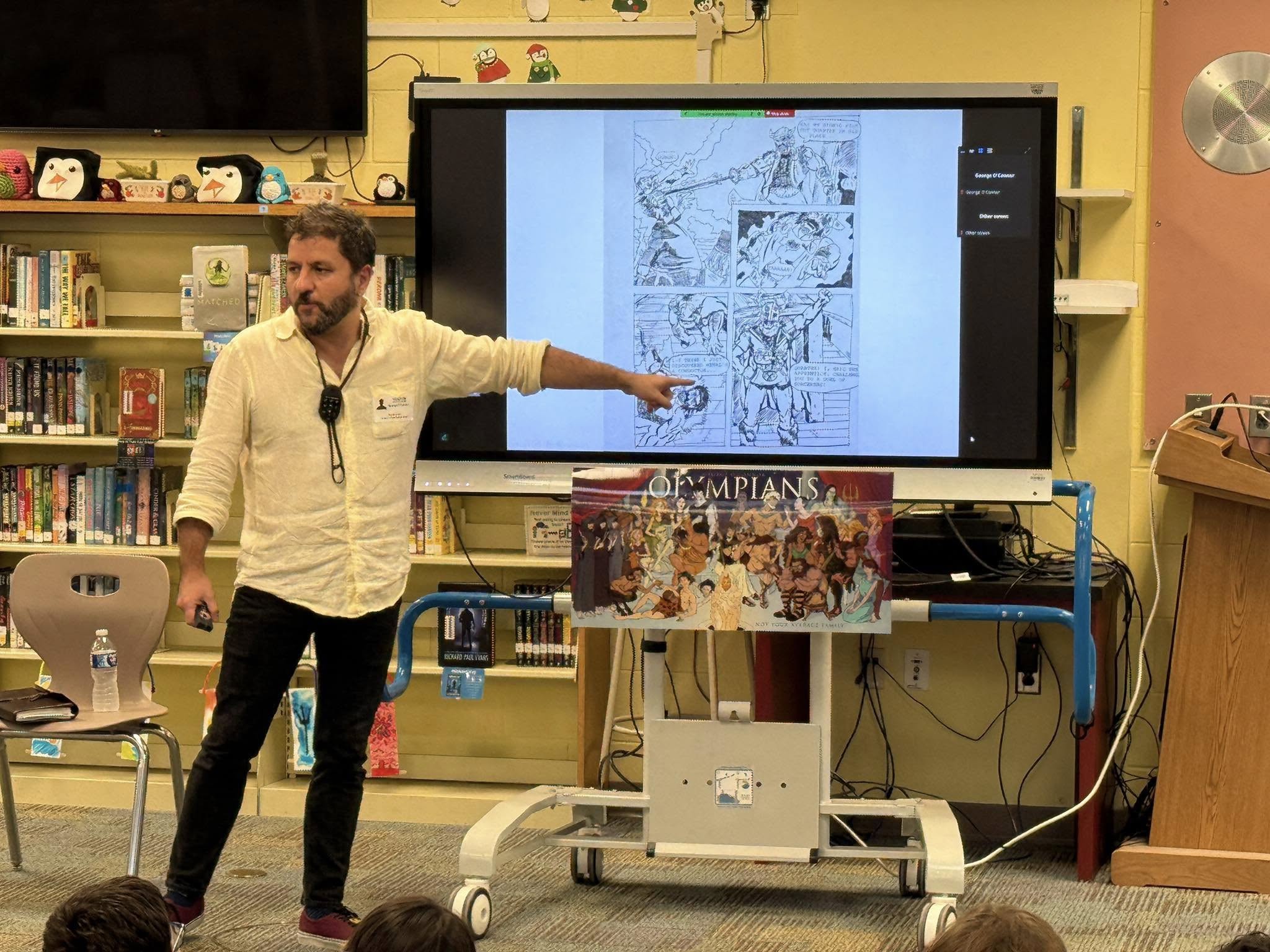

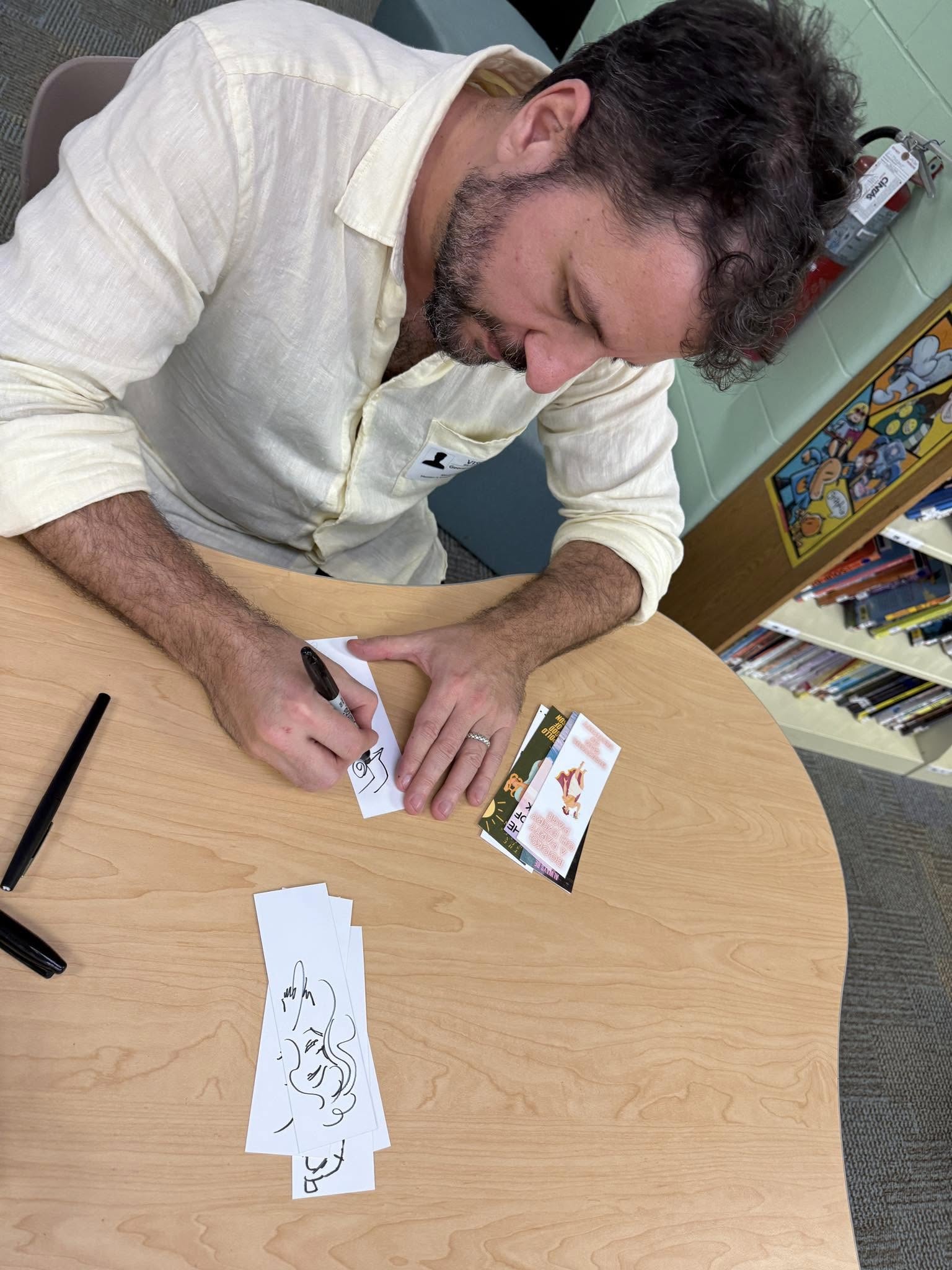

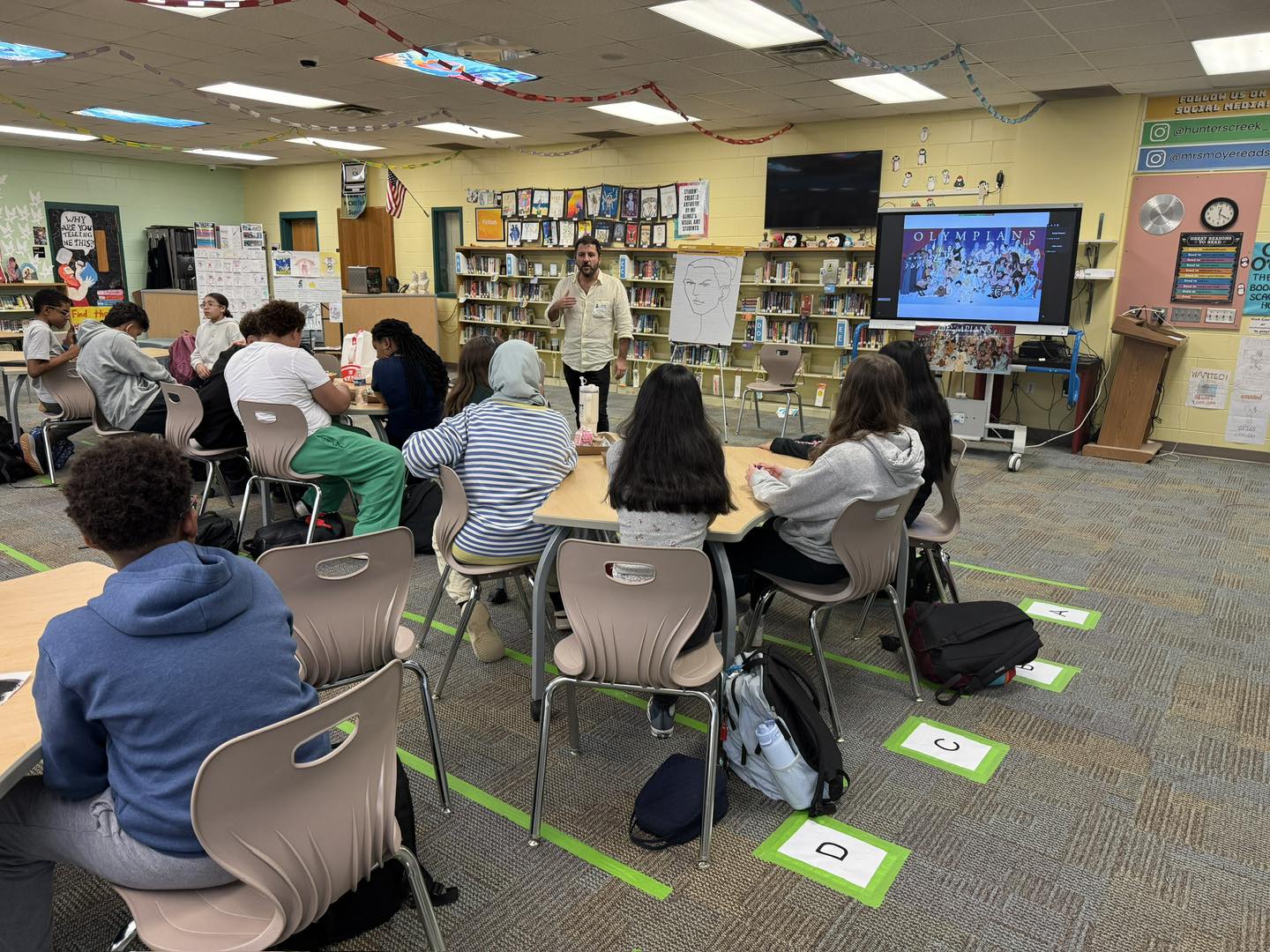

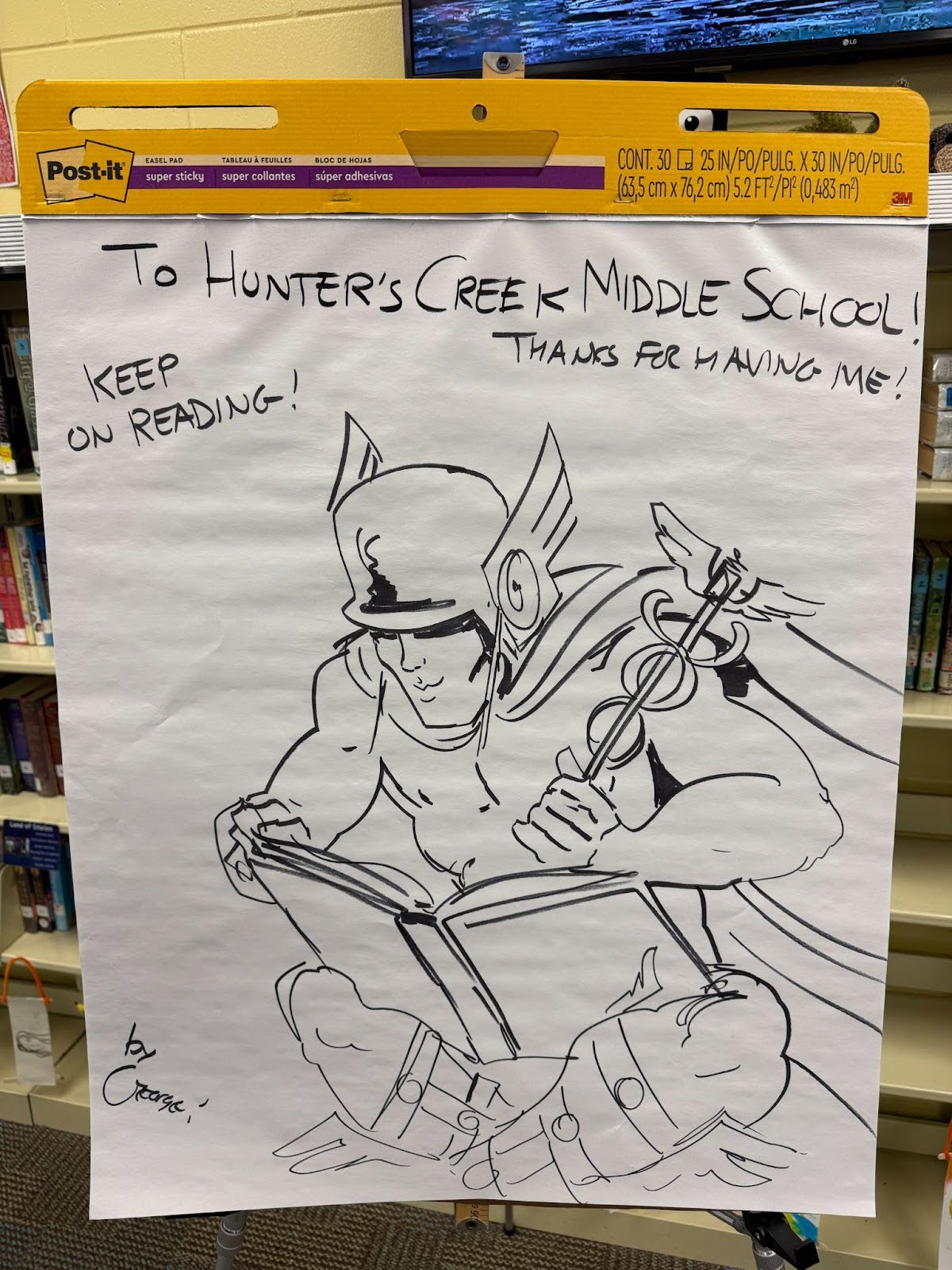

We are so thankful to George O’Connor for being with us all day. Not only did he present to over 1,000 students, he did a signing time for any student who wanted his autograph; he did an author lunch with students who read over 6 of his books; he stayed after school to draw us a special image, finish signing anything left to sign, including bookmarks for each of our Olympians Community Night finishers (our literacy night that we hosted 2 days before his visit), and take pictures with the library team. It was phenomenal!

Here are some reflections from my students after the visit. I asked them to think about what they learned, what they enjoyed, how they were impacted, or anything else they wanted to share:

- I really liked the day. It was a fun experience learning about him and how he became an author.

- I really liked the day! Meeting the author was exciting, and their presentation was inspiring. The workshop helped me think creatively, and I enjoyed sharing ideas with my classmates. It was a great experience that made me love reading and writing even more!

- I liked it. George O’ Conner was funny and I liked how he gave a description of the god’s story.

- I really like how the authors show the process of how they make the books that we read everyday

- he said that we shouldn’t try to erase our mistakes and try to learn from them

- George O’Connor taught me that you have to keep trying for your dreams because he got rejected from a job at marvel but eventually got it.

- My biggest takeaway is that nobody is perfect, and it takes a while to get where you want to be.

- My biggest take away from George O’Connor’s visit is that it’s ok to make mistakes. He talks about even as an adult, and artists, he still regularly makes mistakes, and going over how it is ok to do so was so refreshing to hear in a world where people are so often afraid to be anything but perfect. Really motivating and inspiring!

- My biggest take away was when he told us that he started drawing at such a young age and has always had a passion for the Olympian books he has written.

- An author visit is important because it inspires us to read and write. Meeting a real author shows us that we can be writers too! They share their stories and challenges, which motivates us to keep trying. It makes reading more fun and exciting, helping us appreciate our own creativity!

- This visit was very important because these author visits can really help people get inspired and help them not doubt themselves.

- This visit was important because it made me understand how George O’Connor made his books and his journey in general. It’s important and powerful to have an author visit our school because it gives us a chance to learn from people who have experience in actually making a book.

- His advice about drawing about not being perfect was a HUGE takeaway for me.

- My biggest take away was that nobody is perfect because I draw a lot and I make mistakes and I learned that it is okay to.

- My biggest take away from this visit was that our changing moment in life can happen wherever and whenever.

- My biggest takeaway was that your imagination can take you anywhere in life.

- That it takes a long time to do things perfectly and to achieve something you are want so you have to be patience

- George O’ Connor taught me some very valuable life lessons and made the presentation funny.

- It impacted me because it allowed me to learn more about the writing and illustrating process, something which I didn’t know much about before.

- It helped me understand better on how the author makes his books and connect to the author better which was good.

- I learned some new stuff about Greek mythology that I didn’t know before.

- It helped me understand the whole journey to become an author.

- It’s important to have authors visit our school because it could help people who want to be authors in the future. It could also help someone find a new favorite book or series.

- It is important and powerful to have an author visit the school in order to inspire kids to read more books and make the author more relatable and real, which I think could also encourage kids to pick up books and start reading more.

- This visit was important because he first off is a New York Times best author which is crazy to think that he actually came to our school and that some people really like mythology books and George O’Connor is the best author for that.

- Author visits are important because it can encourage people to read and for people who want to become authors to learn from them.

- I think that it’s important and powerful to have an author visit our school because they can help give us advice and tell their story to people who enjoyed reading their books.

- It was very impactful since I got to see the POV of an author’s life and how he draws!

- This visit impacted me because it let me learn that even New York Best Time Selling authors make mistakes and learn from them to help them grow as a person and author.

- The visit impacted me by showing me how much work goes into these books.

- The visit really inspired me! Hearing the author share their journey made me want to write my own stories. Learning about their creative process showed me that it’s okay to struggle sometimes. The interactive workshop was fun and helped me think more creatively. Overall, it made me excited about reading and writing!

- I thought it was really cool as his upbringing as an author and it is really motivating.

- Having a yearly visit means getting to learn about the lives of authors, how they got to where they are, and what inspires them. This. in turn, inspires me to stay motivated and chase my dreams no matter what goes wrong.

- Yearly author visits mean a lot to not just me but I bet to so many others too because its so cool getting to have a well known author come to our school and tell us their story and their perspective of their own books they wrote.

- Author visits let me meet “famous people” that other people don’t get to meet and I get to meet the authors of the books that I love.

- Having a visiting author yearly is something that excites me and is something for me to look forward to.

- Having a visiting author yearly makes me read more books that I might not have read if it wasn’t for the author visit.

- Yearly author visits mean that kids get to explore different genres and books. Like I did not know who George O’Connor was and I had never read his books but then I read them and now I love them.

- Having an author yearly means a lot to me because they are really inspiring.

- Author visits mean a lot to me because it shows that our school and staff want to put together something fun for us and that they care, Gorge O’Connor also took time out of his day to come see us.

- Author visits educate children; it always makes them more tempted to read more and learn about the author. Also the author can teach us valuable things.

- This visit was important because it helped us see and talk to George O’ Connor in-person, it also helped us learn more about Greek Mythology. It is important and powerful to have an author visit our school because it helps us talk or see our favorite authors and learn more about them. In addition, it also gives us a small break from school.

Another teacher also shared her students’ responses to “What I liked the best was…”

- the way he explained his book and the way he drew ZEUS in 28 seconds; how he is able to make a small period of time into something really cool; When he showed his drawings/drawing fast

- Book signings and pictures with him after school; seeing him at lunch; really enjoyed when I met him because he was really nice and caring

- When he said that nobody is perfect and we can all make mistakes, that was really nice of him;

- My favorite moment from the author’s visit was when he told us the lesson which was like don’t be afraid to make mistakes and fail

- How he used the errors without being scared

- Funny stories; when he was making us laugh

- I love this part because he explains books and explains how he did it. That’s why I love it.

As you can see from the comments and love, my students and I would highly recommend George for a school visit!