“Why Nature is the Best Classroom”

On a crisp autumn afternoon last week at Naturally Nurtured Nature School here in Macon, Georgia, I held two sugar gliders—small, nocturnal, gliding animals that look similar to flying squirrels. They peeped out from a soft fleece ‘bag’, gazing up at me with enormous and curious eyes. The kids gathered round, oohing and aahing. We each got to commune with these exotic creatures, and talk about how, at this very moment, similar flying squirrels were sleeping in the trees and waiting for night to hunt for food. The children had lots of questions and comments. “It was so cool!” “The sugar glider tickled when it crawled on me.” “How far can they fly?”

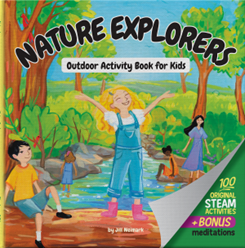

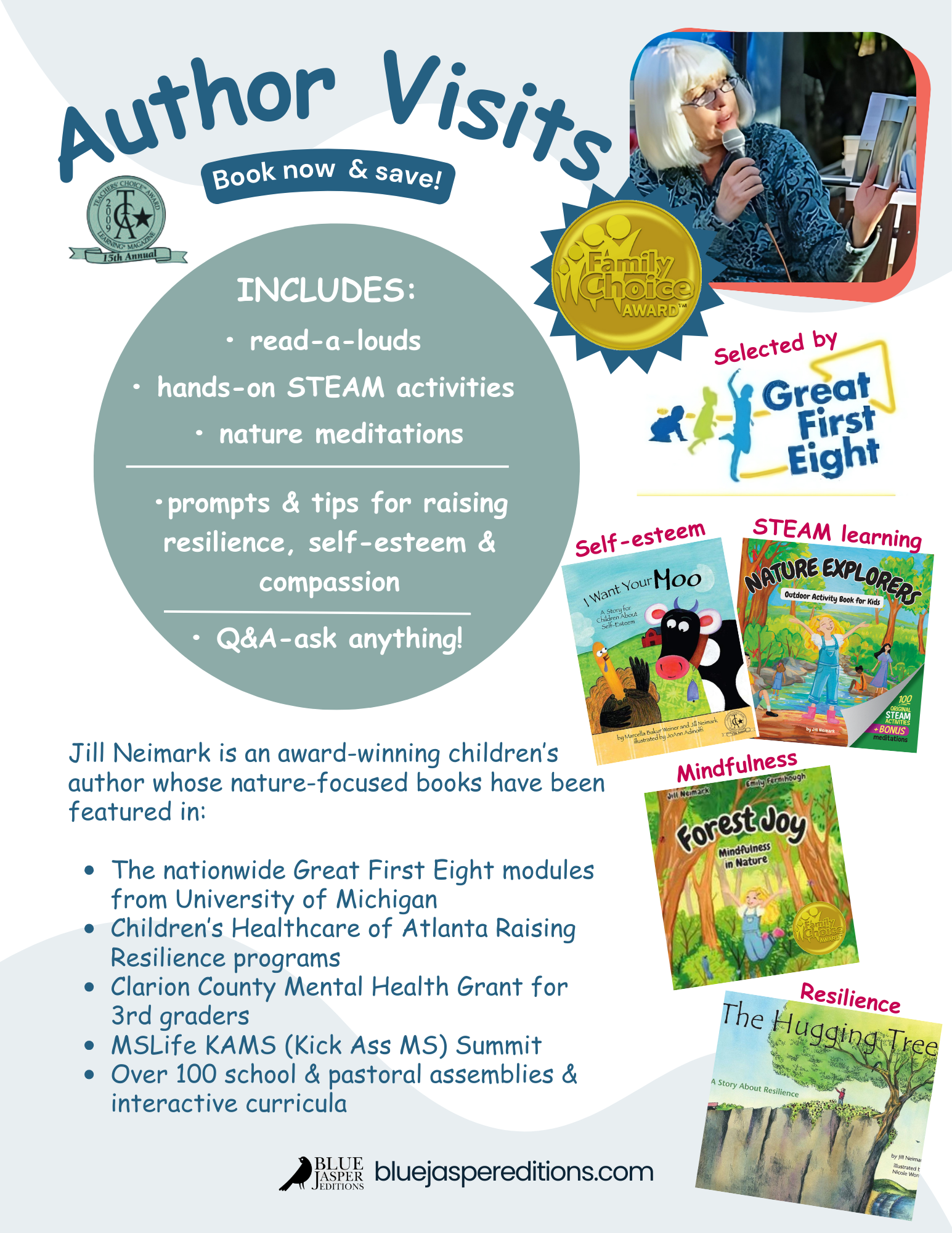

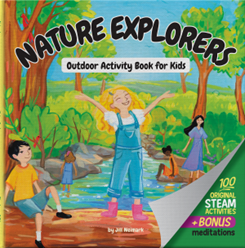

It all happened because the school’s owner, Dawn Willis, and I were planning a class for the kids from my new STEAM activity book, Nature Explorers: Outdoor Activity Book for Kids (Blue Jasper Editions, 2023). We were discussing one of the most basic outdoor activities kids can do, almost anywhere. It’s a kind of gold standard for forest schools. And that is to sit down with a tree and make it your ‘friend’, observing it closely, sketching it, writing down all its features, even decorating it with your own handmade art.

In the book, I had added a storytelling prompt to help the kids with language arts: imagine you’re a flying squirrel named Tom, living in a tree and hunting by night. My book gave the kids a few facts (the squirrels can glide as far as a football field; they can pivot in midair; they huddle in groups to keep warm, they even cuddle with owls sometimes). In a group setting, kids were to gather after a session with their tree friend, and tell a group story about Tom the flying squirrel.

Dawn, ever resourceful, said, “I’ve got a surprise for you!” and ran off to get her two pet sugar gliders, rescued four years earlier. Yes, Dawn has sugar gliders, among many other creatures, from bunnies to frogs to horses.

That led us all to a discussion about what humans can learn from gliding or flying creatures and how creatures like sugar gliders have influenced human flight systems. Just as sugar gliders spread their limbs and use their “patagia” (the flap of skin that stretches between their limbs) to catch air currents, modern aircraft use flaps and winglets to control lift and stability, helping to reduce drag and improve efficiency. Next day’s lesson and activity: design a paper helicopter, and collect different seeds to see how they are designed to ‘fly’ on the wind.

Forest schools like Dawn’s, where learning takes place almost entirely outdoors, are increasingly popular across the globe. And here in the USA, there were over 800 nature-based schools as of 2022. Their popularity is driven by parental concerns over excess screen time, as well as recognition of the benefits of nature-based play. Children today are spending more time inside and on screens than ever before. Studies show that the average kid now spends an average of 7 hours per day on screens, and outdoor playtime has declined by 50% over the last few decades. Many parents want to change that. There are nature pre-schools and forest schools in almost every state now.

Even when kids don’t attend forest school full time, homeschooling parents may send them to a day or two of forest school every week. As of 2023, an estimated 3.7 million students in the U.S. were being homeschooled. Homeschooling parents are often deeply invested in providing their children with diverse learning opportunities, and outdoor play and nature-based education are key components of many homeschool curriculums. According to a 2021 study by Homeschool.com, 72% of homeschooling families reported that spending time outdoors and engaging in nature-based activities were essential parts of their educational plans. These families recognize that outdoor learning enhances academic skills, physical health, and emotional well-being.

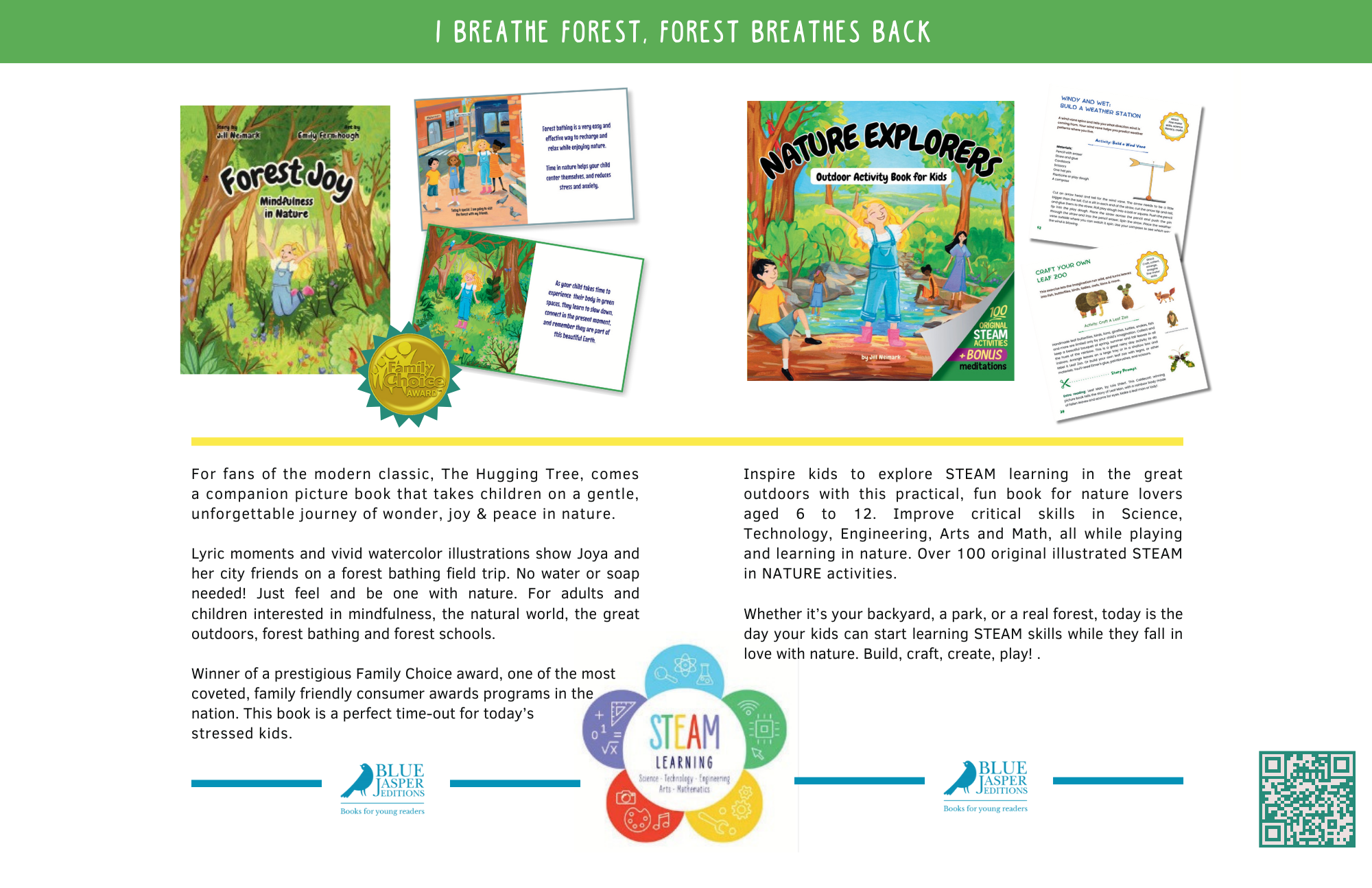

That’s why I started my own children’s imprint, Blue Jasper Editions, and wrote Forest Joy (a picture book on mindfulness in nature) and Nature Explorers (an outdoor activity book focused on STEAM skills), to join in this growing movement to help kids enjoy cross-disciplinary learning and life skills while immersed in nature.

My books join some towering classics in the field, such as Play The Forest School Way and the related series of books, by Jane Worroll & Peter Houghton. These books, which come out of Great Britain and are aimed at middle grade and older kids, give detailed instructions on activities in the ‘bush’, along with instructive line drawings (there are 5 copies in my state’s library system, and they are always checked out).

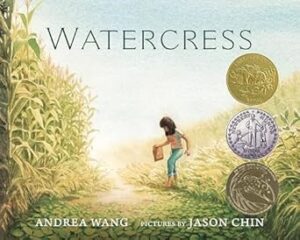

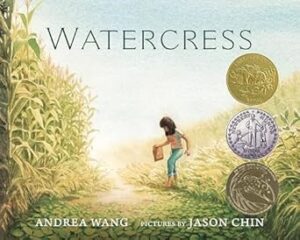

Even the recent Caldecott award-winning picture book Watercress, by Andrea Wang, illustrated gorgeously by Jason Chin, is an homage to the intersection of nature and culture, weaving plants in with identity. In the story, while driving through Ohio in an old Pontiac, a young girl’s Chinese immigrant parents see watercress growing wild by the side of the road, and decide to forage it, cook it, and in that way weave their new world with their old traditions.

Connecting with Nature to Learn and Thrive

When children step outside and immerse themselves in nature, they’re not just playing—they’re learning. Nature offers an endless classroom filled with hands-on activities that stimulate curiosity, self-regulation, adventure and joy. Through outdoor activities, kids can engage in science, language arts, history, and hone their social and emotional skills, all while exploring the world around them. And in play they can connect and develop social competency as well. It’s just easier to bond, to learn to share, when you’re foraging, building, exploring in nature. Nothing substitutes for experience! Learning about flight is one thing. Classroom learning will never match actually holding a sugar glider, learning about its anatomy and how it glides on air currents, examining seeds to see how they utilize wind currents, and building your own paper helicopter.

Here are a few very simple activities from my books you can easily do with your kids or students to get started:

- Take a slow, sensory nature walk. Take children on a sensory walk in the woods or your backyard. Ask them to close their eyes and describe the sounds they hear—rustling leaves, chirping birds, the wind in the trees. Ask them to use a magnifying glass to examine seeds, leaves, flowers, and pine cones, anything they find. Ask them to stand still and smell the air and describe it. Afterward, invite them to draw or write about how it all made them feel. This activity helps kids center themselves and practice mindfulness.

- Collect leaves, and then examine the leaf veins and stomata under the glass. This can be a jumping off point for teaching kids about stomata (pores in leaves), transpiration (did you know trees are constantly moving water up through their roots, trunks, branches, and out their leaves?), and many more activities explained in Nature Explorers. You can then make leaf skeletons with your kids (there are many step by step instructions to be found online, as well as in my book). Then talk about insect skeletons, mammal skeletons, and plant “skeletons”. What do they have in common? What is unique in each? I have some illustrations in the book, but there are many on the internet as well.

- Start a phenology wheel. A phenology wheel is a wonderful way for children to engage with nature and learn about the changing seasons. It’s a circular calendar that tracks natural events, such as plant growth, animal activity, or weather patterns, throughout the year. To get started, get a nature journal and some colored pencils and chalk for your child. Encourage your child to pick a tree or place in the front or back yard, and to observe and record the environment around them every week or month—whether it’s the blooming of flowers, the falling of leaves, the arrival of migratory birds, or the color changes in the landscape. They should record temperature, weather, their own feelings, and sketch what they see as well. As you fill in the wheel together, your child will begin to notice the cyclical nature of life, deepening their connection to the natural world. This hands-on project is not only educational but also fosters mindfulness and curiosity about the environment.

- Create a dreamcatcher. Creating a dreamcatcher from a paper plate is a fun and simple craft that can teach children about different cultural traditions while developing their fine motor skills. Start by cutting out the center of a paper plate, leaving the outer ring intact. Punch small holes evenly around the edge of the plate and have your child weave yarn or string across the circle, looping it through the holes to create a web-like pattern. For added decoration, tie colorful feathers and beads to the bottom of the dreamcatcher. You can hang the finished dreamcatcher above your child’s bed or in a window as a creative way to introduce them to the Native American tradition of dreamcatchers, believed to catch bad dreams and let good ones pass through. At forest school, Dawn works with the kids to make dreamcatchers out of vines they collect from wooded areas and weave together. If you’re feeling inspired, you can do the same with your child. The circular nature of the dreamcatcher can lead you into discussions of geometry, sundials and many other areas for exploring science, culture, history and art.

- Unleashing Readers note: Please make sure to build this foundation around indigenous folks and honoring their beliefs and traditions.

- Hold a tea ceremony in nature. Spread a blanket, gather a group of children, and hold a tea ceremony. While drinking tea and perhaps eating some tasty treats, think of ways to thank the sky, trees, flowers, rivers, and earth for all they give. When the tea ceremony is over, pour the last little bit of tea into the earth and say together, “Thank you trees. Thank you sky. Thank you earth. Thank you, green good world.”

(illustration from Forest Joy)

The Power of Outdoor Learning

By encouraging kids to spend more time outdoors, we can help them cultivate the tools they need to thrive in an increasingly busy, digital world.

Students who participate in cross-disciplinary learning activities show improved problem-solving skills and higher engagement levels. By linking different subjects, such as having kids learn about seed dispersal while practicing engineering principles through the design of paper planes, they not only deepen their understanding but also enjoy the process. This engagement makes learning more enjoyable and can lead to long-term retention of the skills they acquire.

Parents value how outdoor education promotes active, hands-on learning that engages children in subjects like science, math, and language arts in ways that traditional indoor classrooms may not. And for those whose kids are happy in standard schools, or who don’t have the extra funds or time to add in a few days of forest school every week, books like Forest Joy and Nature Explorers offer an accessible way for families to integrate nature-based activities into a solid curriculum, helping their children develop essential skills while fostering a deeper connection with the natural world.

You can purchase either one of my books here on Amazon:

Forest Joy: https://mybook.to/jSfWIIO

Nature Explorers: https://mybook.to/beEaeQe

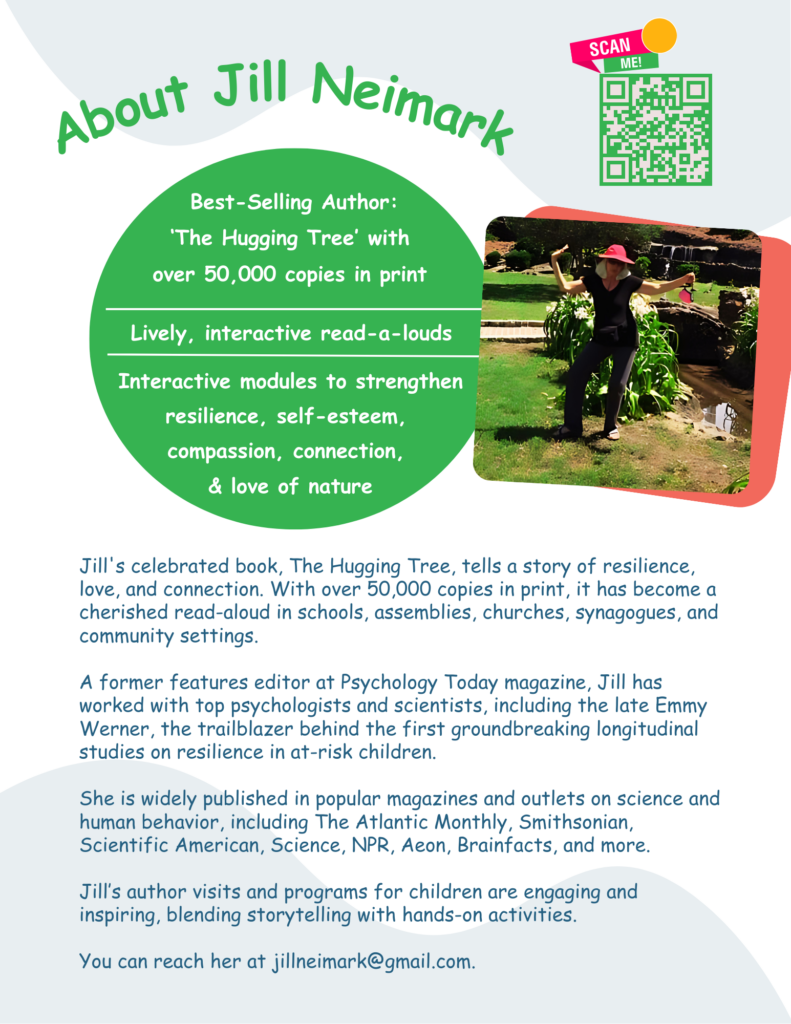

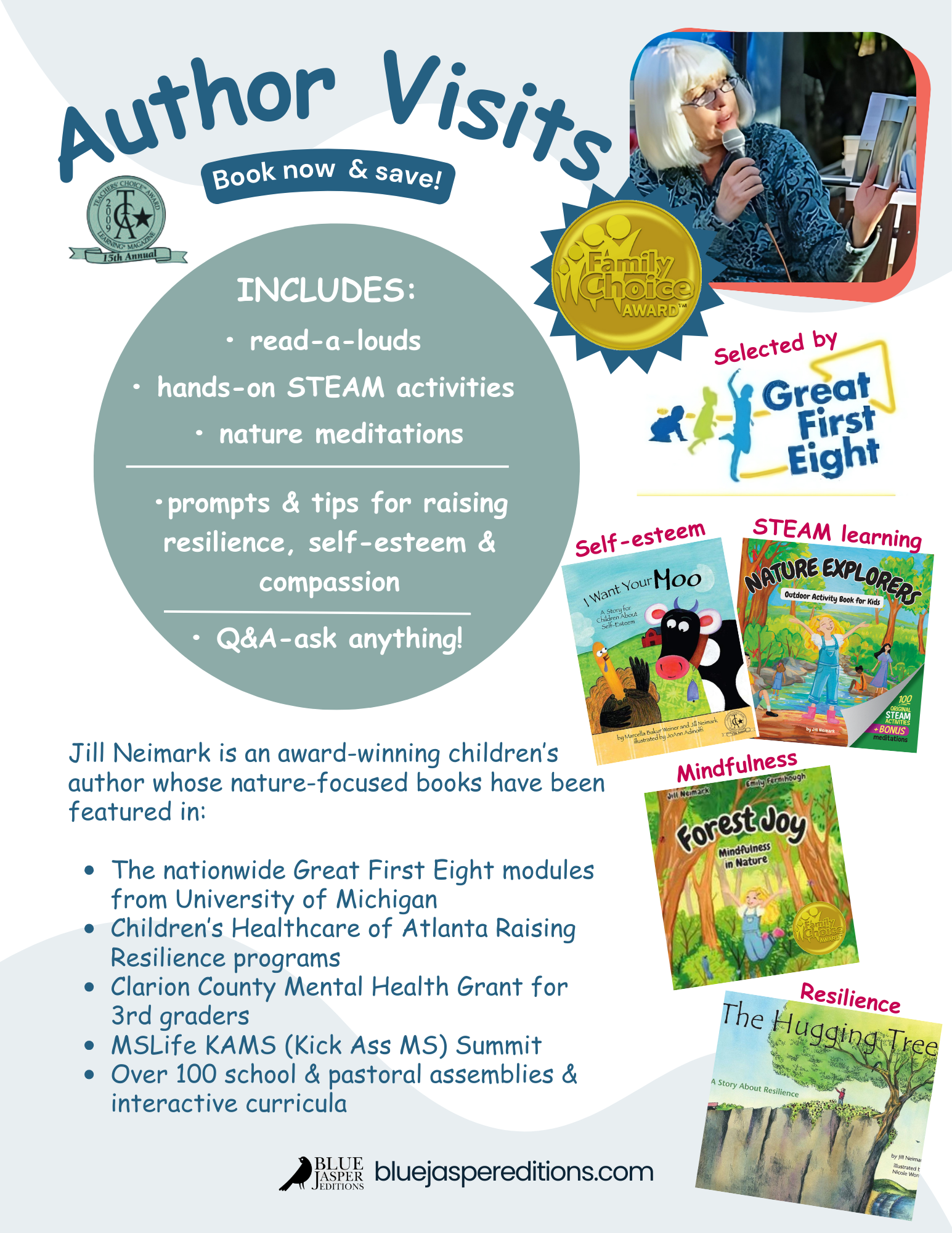

About the Author: Gillian (Jill) Neimark is an author of adult and children’s fiction and nonfiction, as well as a prolific science journalist. She has published poetry, essays and reviews in numerous literary magazines. Her picture book, The Hugging Tree (Magination Press) is a bestseller and was selected by University of Michigan’s First Great Eight Program for their environmental stewardship module. To read more about her you can access her website: https://www.jillneimark.com and to read more about her new children’s imprint, visit https://www.bluejaspereditions.com

Thank you, Jill, for sharing all of these fun ways to bring the classroom to nature!