When An Academic Write Fiction

I adore stories. I want to listen to them, watch them, write them, tell them, and live them. Publishing a novel, is truly a dream come true because I can’t wait to share one of my stories with the world. As a college professor of communication, however, I’ve also spent countless hours and pages (over)analyzing stories, themes, and characters.

So, what happens with someone who teaches gender and culture writes fiction? I felt some added pressure to think critically about the characters I was creating and what kind of potential impact they could have on the kids who would read about them. At the same time, I know it’s impossible to avoid all common tropes and stereotypes.

In addition to my forthcoming novel, I am also co-editor of a recently released Gendered Identities: Critical Re-readings of Gender in Children’s and Young Adult Literature (Routledge 2016), and one of my primary areas of study is communication and culture, which means I really should know better. I do know better, but what happens when theory meets practice?

When I teach popular culture in the media, I encourage students not only to analyze messages but also to attempt to create popular culture artifacts such as an advertisement. It forces students to consider what social constructions and stereotypes they rely on.

The goal isn’t necessarily to avoid all stereotypes because it’s not necessarily possible or realistic. My hope is that we become a little more active in the process of seeing how things like gender and culture are presented in our characters. In my case, at times, both my editor and I took a step back a few times to ask what was necessary to the story versus what might have been a description that only belonged in my head. I may have wanted to deal more overtly with some of the issues, but they weren’t central to this particular story which is focused on grief. Sometimes, it added an unnecessary layer to explore a cultural dimension.

That doesn’t mean books like The Haunted House Project aren’t important to discuss in relationship to those themes. Even when stories aren’t really about gender or culture, they are still telling kids what’s normal and what’s expected of them.

Here are a few things that writers, readers, teachers, and parents can think about:

Character Interests

Yes, many boys like to play sports, and many girls like make-up. But if that’s ALL we see, it can limit the possibility for kids to think outside of a rigid expectations. Having a range of characters with a variety of interests and activities can go a long way to alleviate this. It doesn’t mean that all girls in the story need to be math geniuses or that the boys should love to cook, but if kids can see options, it doesn’t pigeon-hole them.

Appearance

We probably talk more about this than any other aspect of gender and culture. Across all genres of popular culture, we critique the overt emphasis on physical beauty for women and girls. It creates unrealistic standards that influence self-esteem. Boys face problematic portrayals as well. In movies and television, boys are expected to be tough, tall, and muscular. Young adult and children’s literature deviates a bit, likely because it’s a time when young men are still developing, but then descriptions focus on perfect hair and eyes, for example. In a world of budding romance and descriptive writing, it’s not surprising that appearance is used to explain attraction.

Language and communication

Generally, for boys, expression of emotions is limited to anger and frustration, and open and honest communication about feelings is practically taboo while girls are more “emotional” and may cry more often.

Girls tend to me more willing to talk about relationships and their feelings as well. That may reflect reality for many people, but it certainly offers opportunities for students to address what is okay in relationships between friends and family members.

If a book (yes, even my own) does rely too heavily on these kinds of boxes, perhaps, students can be trained to see it and to call it out in their reading.

- Even if, or maybe especially when, the themes of the book don’t center on gender or culture, pose questions in readings guides and discussion that help students draw make implicit assumptions more explicit.

For example, questions surrounding The Haunted House Project might include:

- Why do you think Andie’s sister worked as a waitress?

- Isaiah is openly described as geeky. Are those characteristics consistent for both boys and girls? Are girl geeks different than boy geeks?

- Engage students in an exercise where they are challenged to write a short story without using any gender stereotypes. They will probably fail, and that will open up a great opportunity to discuss why we rely on them and what positive purposes they can serve.

- Challenge students to find problematic descriptions of characters that may limit the way they are visualized by readers.

- Ask students how characters might communicate with each other differently if they switched genders or cultures.

In many ways, children’s literature is probably more open to bending and twisting cultural expectations than other storytelling genres. Worlds aren’t as set in stone as they might be for older audiences.

It’s the perfect time for kids to start digging into all the social norms that go unstated in books they read. Not only does can it give them better critical reading skills, they can better understand their own relationships as a result.

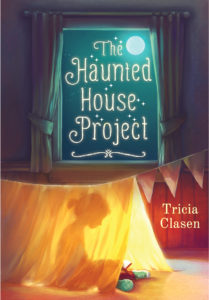

The Haunted House Project

Author: Tricia Clasen

Published October 11th, 2016 by Sky Pony Press

Summary: Since her mom died, Andie’s family has crumbled. Instead of working, her dad gambles away insurance money, while her sister, Paige, has put her future on hold in order to pick up extra waitressing shifts. Andie’s afraid of what will happen if people find out just how bad things are. She’s not sure how long she can hide the fact that there’s no food or money in the house…or adults, for that matter.

When her science partner suggests they study paranormal activity, Andie gets an idea. She wants a sign from her mom—anything to tell her it’s going to be okay. Maybe the rest of her family does too. So she starts a project of her own. Pretending to be her mother’s ghost, Andie sprays perfume, changes TV channels, and moves pictures. Haunting her house is Andie’s last hope to bring her family back into the land of the living.

For anyone who loved Counting by 7s, The Haunted House Project is a journey through loss and grief, but ultimately a story of hope and self-reliance. As much as Andie has been changed by her mother’s death, the changes she makes herself are the ones that are most important.

About the Author: Tricia Clasen is a professor of communication with specialties in public speaking and pop culture and a research focus on critiquing young adult fiction. Always a lover of a good story, she grew up spending her days reading and dreaming of being a writer. This is her debut novel. She and her husband live with their two girls in Janesville, Wisconsin.

Thank you for the insight!

I think Tricia raises a great point here – striving to limit the the use and acceptance of stereotypes in writing is vital, but ensuring that young readers can identify, challenge and work through stereotypes is perhaps even more important. Stereotypes can change over time and differ from culture to culture, but all can be hurtful and damaging, so it’s vital that kids feel prepared to challenge and work through them whenever they find them. Thanks for a fascinating post!

I agree! I thought this post was especially thought-provoking.