“Why I Write Science Books for Children”

One day some years ago when I was writing scripts for the Children’s Television Workshop science series 3-2-1 Contact, I took my four-year-old daughter to my office and introduced her to the show’s actors. Afterwards, she looked at me and said, “I didn’t know they were real.” I was astounded. She had learned from watching Sesame Street and the show I was working on–the only TV shows we allowed her to watch–that what you see on TV is pretend. Big Bird, Cookie Monster and the other muppets were imaginary characters. Sesame Street was an imaginary street. My little daughter had learned the difference between fact and fiction.

From toddler age, children are fascinated by the real world. I consider them budding field biologists. They pick up the tiniest pieces of their environment–a pebble, a shell, a feather, a blade of grass–and excitedly present it to their parent or caretaker. As soon as they can, they repeatedly ask “Why?” About everything! These questions are the beginning of scientific curiosity. And it is my hope that my books tap into and nourish that curiosity.

By third grade, most children have learned about the two literary genres, fiction and nonfiction. The books I write are nonfiction–science, nature. When people ask me why I write nonfiction, I have two answers: First, I am fascinated and excited by the complex interrelationships among animals, plants, microbes, soil, sun and water that hold ecosystems together. Secondly, what goes on in nature is more fantastic, more bizarre than anything science fiction writers have imagined. Sex-changing fishes, flowers that use trickery to attract pollinators, insects that look like leaves and sticks, symbiotic partnerships between totally different species, and creatures that live in water hot enough to melt lead–these and many more are all real!

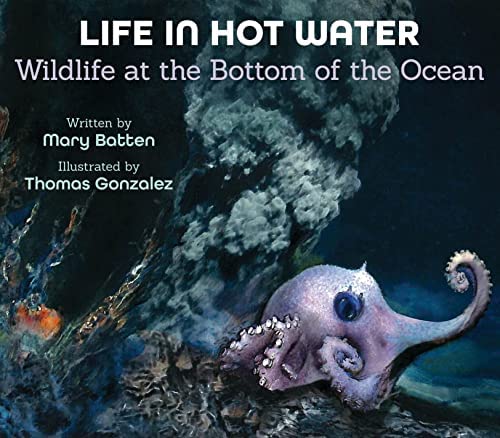

My newest book, Life in Hot Water: Wildlife at the Bottom of the Ocean, is about animals that live in the hottest, most extreme environment on Earth–hydrothermal vents. It is the second book in a series I created called “Life in the Extreme,” about the incredible ability of living things to evolve and take up residence in nooks and crannies of the most extreme environments. Discovery of hydrothermal vents in 1977 is one of the greatest adventures in science.

Hydrothermal vents are underwater hot springs that form along the mid-ocean ridge, the longest mountain range on Earth. You can’t see it because it’s at the bottom of the sea. There it snakes more than 40,000 miles (65,000 kilometers) around the planet. When scientists first descended into this world, nobody expected to find any living thing. But the porthole of their tiny submarine revealed fish, clams, shrimp, crabs, and giant red-tipped tube worms never seen before. How could anything live amidst plumes of superhot, toxic liquid gushing from strange chimney-like structures?

Like toddlers who develop by asking questions, scientists also gather knowledge by asking questions and searching for answers. Questions open doors to discovery and the mind-blowing discovery of hydrothermal vents raised many questions. One of the most important was, “What are these creatures eating?”

Until vents were discovered, scientists thought that green plants and the sun were the base of all food chains–a process called photosynthesis. But no sunlight reaches the total darkness of the vent world miles below the ocean’s surface. And no green plants grow in this world. What then?

Following up these and other questions, scientists discovered an entirely new food chain–one that depends on energy from the Earth instead of energy from the sun. Amazingly, vent animals eat bacteria that feed on toxic chemicals such as hydrogen sulfide, which smells like rotten eggs, spewed from Earth’s interior by undersea volcanoes that create the vents. Scientists called this process chemosynthesis. Robert Ballard, the oceanographer who discovered where the sunken ship Titanic lay, called it “Probably one of the biggest biological discoveries ever made on Earth.”*

Textbooks had to be rewritten to include chemosynthesis as well as photosynthesis. Today research to learn more about hydrothermal vents is going on all over the world.

For me, one of the joys of writing nonfiction is reaching out to scientists who are doing the real work and interviewing them. One of the scientists whom I consulted for this book, Dr. Janet Voight, Associate Curator at the Field Museum in Chicago, said, “There’s so much about the deep sea that we haven’t even begun to explore. It’s all discovery, and that makes it exciting.”

Children are natural born explorers. Tapping into their questions is one of the most exciting and productive ways to foster children’s developmental curiosity, engage them in the basic scientific process, and encourage them to write their own nonfiction. Children’s science books, such as Life in Hot Water, can be used to create multi-disciplinary units engaging biology, geography, art, and creative writing.

*Bill Nye discusses discovery of hydrothermal vents with Robert Ballard: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D69hGvCsWgA

Published June 21, 2022 by Peachtree

About the Book: .A dramatic overview of the deep-sea extremophiles that thrive in scalding water and permanent darkness at the bottom of the ocean

The scalding-hot water gushing from vents at the bottom of the ocean is one of the most extreme environments on Earth. Yet over millions of years, many organisms—from chemical-eating bacteria to eyeless crabs and iron-shelled snails—have evolved in amazing ways that enable them to thrive in this unlikely habitat. Scientists are hard at work to learn more about the complex ecosystems of the ocean depths.

Award-winning science writer Mary Batten and NYT best-selling illustrator Thomas Gonzalez, the masterful duo that created Life in a Frozen World, team up again in this impressive overview of hydrothermal ocean vents. Her clear, informative text coupled with his unique and eerily realistic paintings of sights never seen on land—gushing “black smokers,” ghostly blind shrimp, red-plumed tube worms—will entice readers to learn more about this once-hidden world at the bottom of the sea.

About the Author: Mary Batten is an award-winning writer for television, film and publishing. Her many writing projects have taken her into tropical rainforests, astronomical observatories, and scientific laboratories. She scripted some 50 television documentaries, was nominated for an Emmy, and is the author of many children’s science books, including Aliens From Earth, and Life in a Frozen World: Wildlife of Antarctica. Her most recent book is Life in Hot Water: Wildlife at the Bottom of the Ocean.

Thank you, Sara at Holiday House, for connecting us with Mary!

1 thought on “Author Guest Post: “Why I Write Science Books for Children” by Mary Batten, Author of Life in Hot Water: Wildlife at the Bottom of the Ocean”