“Guide Them like Lighthouses to the Shores of Success”

When I was in second grade, I considered myself to be the dumbest kid in my class. I came to this rather tragic realization when my teacher instituted a math exercise where we would be given a sheet of fairly simple math equations and a time limit. Those who finished the series of equations before the time was up received a sticker that was placed in front of our name on a very pretty poster board display. Every successful completion within the time limit resulted in another sticker. Some of my classes finished every single math quiz within the time limit and had the unstoppable line of stickers to prove it. Other kids missed the occasional day, but overall, had a fairly mean lineup of stickers. There were other kids still who struggled but achieved the occasional sticker, and I’m sure the few they possessed meant a great deal to them.

And then there was poor, dumb Preston who had not a sticker in the world.

At this point, my teacher must have realized her error because she began the practice of “skipping” days. Whenever she skipped a day—and we did not have one of these timed math quizzes—everyone got a sticker. I finally had my sticker. There was only one problem: I knew I hadn’t earned it. As the school year progressed, more and more of these “skip days” occurred, and before I knew it, I had enough stickers to hide from the untrained eye the fact that I had not earned a single one of these on my own. None of my second grade peers made fun of me for how few stickers I had. But that didn’t change the fact that I had earned a tremendous new bully: myself. Nothing tanks one’s self-esteem more than knowing you’re the dumbest kid in the class and having the stickers (or lack thereof) to prove it.

I wish I could tell you that this was the origin story of how I went on to become the world’s greatest mathematician. Alas, this is not that story. I wager my math skills to this day are only marginally better than the fifth graders to whom I teach (environmental science). Math is not something I was born to be good at. This is not to say I think one needs to be born good at something in order to succeed at it. But I do think we are born with innate interests and desires. And the sooner we can key into what these things are, the sooner we can unleash a world of potential, either in ourselves, or—in the case of teachers—from these young minds whom rely so deeply upon the light of our learning. As teachers, we can—and should—guide them like lighthouses to the shores of success. Now I realize, as a children’s author, that I am a somewhat biased source, but I can think of no better beacon than the power of literacy and books.

Flash forward to the Scholastic Book Fair.

As a second grader—even one with zero stickers (real ones anyway)—the allure of the Scholastic Book Fair was powerful. Born into a relatively low-income family, I had enough money to buy one book—a single book—and as such, I had to make it count. The book I settled on was one about dinosaurs. I was probably eight years old. Of course, I liked dinosaurs. This purchase was made purely on the appeal of the cover with absolutely no understanding of the sort of book I was walking into. And that was nonfiction. Now, as someone who adores nonfiction, I can tell you with certainty that I was ill-equipped with the literacy required to tackle such a read. What essentially happened was I would “read” the words on the page and have zero comprehension of what I’d just read. It was the most surface level act of reading with none of the understanding behind it. This could have been a relatively painless failure, if not for my cousin Tobin—in the same grade as me—who bought the exact same book as me. And let me tell you, he was simply gushing with newly learned dinosaur facts. Hey, Preston, did you know that a stegosaurus was roughly 30 feet long, weighed 11,000 pounds, but only had a brain the size of a dog’s? Oof. I suddenly felt a terrible kinship to stegosauri.

Needless to say, I felt pretty defeated. The thought occurred that if couldn’t even understand a book someone else my age was reading for enjoyment, I might never amount to anything. This is a terrible thing for an eight-year-old to feel.

I may have been my own worst enemy, but I did have someone in my court: my mom. As a lover of books and even writing, she knew I had the desire to read—even if I hadn’t found the right book just yet. With that said, she’d heard a thing or two about this spooky book series called Goosebumps. And so, as I entered the third grade, to a brand-new school, a new start, and a slightly lower than normal self-esteem, she hooked me up with my very first one: Goosebumps #2: Stay Out of the Basement.

Holy f***ing s***! What the f*** was I reading? I had no idea—it was weird as s***—and I was here for it. Their dad was a f***ing plant monster thing? Hell yeah! And thus, I fell down the slippery slope of a book series with just way too many books and where every chapter ends on a cliffhanger.

I wasn’t long before my mom had realized her child’s sudden new hobby was about to get expensive. And so, without further ado, she introduced me to the library. While there were plenty of Goosebumps to spare, I burned through these faster than a teenage boy burns calories. At a certain point, I was forced to redirect my attention elsewhere. I had a great science fiction run with the works of Bruce Coville. But perhaps no chapter book had a greater impact on me than Bunnicula: A Rabbit-Tale of Mystery (1979).

The premise is this: a family called the Monroes has a pet dog, Harold (the narrator), a pet cat named Chester (a vaguely paranoid orange tabby who loves literature and milk), and a brand-new pet rabbit—the titular Bunnicula—who may or may not be “sucking the life” out of vegetables. I can tell you the exact moment when this novel changed my life. Keep in mind that this is a recollection of events from the nostalgia-fueled memory of a thirty-eight-year-old, who has not reread the novel since they first read it as an eight-year-old (give or take). Picture this: Chester, jealous of all the attention the family bunny has been receiving of late, is contemplating an attempt on Bunnicula’s life. After reading that vampires can be slain by pounding a stake through their heart, Chester interprets this murder weapon as a juicy slab of steak, which he removes from the fridge, proceeds to throw on top of the bunny, and then hops on top of it, attempting to somehow pound it through this poor rabbit’s heart.

“I think it’s supposed to be sharp?” Harold asks (according to my memory).

“Of course, it’s sharp,” says the version of Chester who lives rent-free in my head. “It’s sirloin.”

Somehow, someone had forgotten to pass on the memo to me that books could be funny. This was undoubtedly the funniest thing I had ever read. To this day, it might still be! And it was in this moment, when a moment of humor conveyed through written word irrevocably tripped a dopamine neurotransmitter in my brain, flooding it with hysterical euphoria, that I came to a life-altering realization: I wanted to write.

When I was maybe eleven years old, I attempted to write my first novel. It was about a dog and a cat who get lost in Australia and befriend a dingo. I maybe wrote a chapter or two before I quit. Whether or not it was a good chapter or two is inconsequential. What it was instead was an important chapter or two—perhaps the most important chapter or two I’ve ever written—because it taught me one of the most powerful lessons that eleven-year-old me could learn: I could write. I could tell a story. I had stories inside of me that I wanted to tell.

When I was fourteen years old, I made another attempt, this time in the fantasy genre, of which I was growing quite fond. I got further this time; wrote more pages, more chapters. Did not finish.

I made another attempt again when I was sixteen years old, and this was an important one. Because I did not stop. I kept writing. Maybe on and off, but I kept on going, even when I turned seventeen.

When I was eighteen years old, I finished the novel that I started when I was sixteen: a high fantasy novel called The Mark of Mekken, starring a young protagonist named Aidan Cross. Once more, whether it was good or not is far less consequential than how important it is to me. Amidst my (failed) attempts to publish it, I asked for publishing advice in a fan letter I wrote Christopher Paolini, of whom I was a big fan at the time. Paolini’s success at such a young age was endlessly inspirational to me. To my surprise and delight, Paolini wrote me three pages of letters back in encouragement. Oh, and he also recommended me to his agent, Dan Lazar, who would keep an eye out for my manuscript! I’ll spare you the suspense: Dan Lazar did not sign on to represent my novel. But he did write me the most encouraging rejection letter I have ever received, particularly in regard to my protagonist, Aidan, whom he hoped would succeed on his journey.

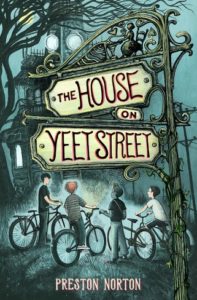

Some eagle-eyed readers might recognize that my major middle grade debut, a queer ghost story called The House on Yeet Street—to be published August 27, 2024 by Union Square Kids—also features a protagonist named Aidan Cross. This is not by coincidence. The House on Yeet Street might be middle-grade horror—perhaps not so distant from the Goosebumps stories that inspired it and, indeed, changed my life—but it is also a story about creativity and identity and how closely the two intertwine. In The House on Yeet Street, my thirteen-year-old MC, Aidan Cross is writing a fantasy love story starring a fictional version of his best friend, Kai Pendleton—reimagined as a merman named Kai Pendragon—and a genderbending version of himself named Nadia (Aidan spelled backwards). When I originally pitched this MG book idea to my agent and editor, it was with three other ideas, two of which I was convinced would be selected over it. Not only was I surprised that The House on Yeet Street floated to the top, but I was also elated, especially as it has easily turned into the personal favorite and possibly most personal of all my novels. It has also caused me to reflect on the version of Aidan Cross I wrote all those years ago and the queer subtext I may or may not have fully understood in his story and my own.

I know what you’re thinking: what does this have to do with teachers? To which I would reply: everything! I would also pose the question: who is a teacher? Or better yet: who can be a teacher? To which I would reply: everyone. A teacher can be a mom, an author, even a literary agent. I believe a teacher can even be a book—even one about monster plant dads and vampire bunnies. What better teacher than the one who is born inside a child’s mind? There is a reason evil and ignorant people across the nation are organizing to ban books—of all things—from children, even as the whole entire internet sits at their fingertips. It is much easier to stop a child from becoming literate and learning to think independently—by carefully censoring and curating their access to literature and ideas—than it is to stop a young person from thinking for themself once they have learned how to do so.

To teachers, to librarians, to every adult with a child in their life: don’t stop shining your light. These children see you. These children need you.

The future needs you.

Publishing August 27th, 2024 by Union Square & Co.

About the Book: A hilarious ghost story about a group of thirteen-year-old boys whose friendship is tested by supernatural forces, secret crushes, and a hundred-year-old curse.

When Aidan Cross yeeted his very secret journal into the house on Yeet Street, he also intended to yeet his feelings for his best friend, Kai, as far away as possible.

To Aidan’s horror, his friends plan a sleepover at the haunted house the very next night. Terrance, Zephyr, and Kai are dead set on exploring local legend Farah Yeet’s creepy mansion. Aidan just wants to survive the night and retrieve his mortifying love story before his friends find it.

When Aidan discovers an actual ghost in the house (who happens to be a huge fan of his fiction), he makes it his mission to solve the mystery of Gabby’s death and free her from the house. But when Aidan’s journal falls into the wrong hands, secrets come to light that threaten the boys’ friendship. Can Aidan embrace the part of himself that’s longing to break free…or will he become the next victim to be trapped in the haunted house forever?

About the Author: Preston Norton teaches environmental science to fifth graders. He is the author of Neanderthal Opens the Door to the Universe, Where I End & You Begin, and Hopepunk. He is married with three cats.

Thank you, Preston, for this reminder that we are guides to the kids in our lives!

1 thought on “Author Guest Post: “Guide Them like Lighthouses to the Shores of Success” by Preston Norton, Author of The House on Yeet Street”